ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO – With the discovery of twenty-nine buried cars at significant sites around the world, one would think Japanese archeologist Ryoichi would be a household name. He’s not. Instead, the creator of Ryoichi, American photographer, Hollywood set designer, and visual storyteller, Patrick Nagatani, is the name to remember.

Born in Chicago in 1945 to Japanese parents, Nagatani was raised in a Christian household. According to the Densho Encyclopedia, “His parents, John and Diane Nagatani, were imprisoned in different camps during World War II and relocated separately to Chicago, where they met, married and started a family, raising their son as a Catholic in a primarily Polish neighborhood in the Midwest. Nagatani attended UCLA, graduating with a Masters of Fine Art.

Influenced by his mentor, Robert Heinecken, “Nagatani decided to disregard ‘photographic truth’ and to seek what he calls ‘the façade of representation’”. Some call the style “magical realism.” Patrick went on to become one of the modern originators of directed photography, a style that stages a photo much like a set of a movie, using design techniques and drama-like production.

In 1987, Nagatana moved to New Mexico to focus his art on political, personal, cultural, and environmental themes. He began to teach at the University of New Mexico the same year, staying until his retirement in 2006. While at UNM, Nagatani received many awards and accolades.

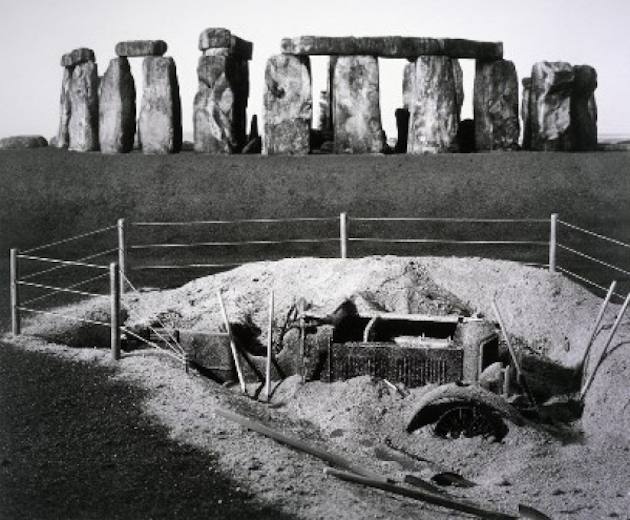

Since his death on October 27, 2017 at age 72, Nagatani has seen a resurgence of interest in his work as three new exhibits attest, two in Albuquerque and one in Santa Fe. Patrick Nagatani: Invented Realties is housed at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. Invented Realities is a “survey across the late artist’s rich career”. Patrick Nagatani: A Survey of Early Photographs “tracks Nagatani’s development from when he first began creating photographs through and beyond graduate school…” Early Photographs is on display at the University of New Mexico Art Museum [6]. And Excavations: Buried Cars and Other Stories is on view at the Albuquerque Museum of Art. Excavation “focuses primary on Nagatani’s Excavation series, documenting the purported excavation of 29 automobiles buried at energetic power sites around the world…”.

I was able to attend all three exhibits. And though the exhibits are amazing with a unique emphasis, I found myself gravitating towards Excavations for its humor, story telling, and scope of work. In Excavations one finds Nagatani’s work on Buried Cars, as pointed out, a make believe story Nagatani created and staged about a Japanese archeologist who discovered cars around the world. One also finds an assortment of his popular work such as Japanese Children’s Day Camp, a work highlighting Japanese internment, Tewa Ritual Clowns, a work juxtapositioning Native dancers with bomb in the background, and Trinitite, Ground Zero, a photograph showing trinitite falling from the sky at the infamous Trinity Site in Southern New Mexico. There’s also a couple of pieces he did in conjunction with painter Andree Trace and another photographs of airplanes connected to a story Nagatani created about women pilots entitled The Race.

As I perused the Excavation exhibit I found myself eavesdropping on Nagatani’s former assistant as he was telling a group of people about Buried Cars. The story is make-believe, but due to the intricate nature of the project (photographing, journals, map making, sample collections, etc.) many people believe that there really is an archeologist named Rioucyi who found buried cars throughout the world.

And during a lecture at the opening of the Excavation exhibit, Dr. Joseph Traugott gave the presentation as if Ryoichi and the archeological sites were real, tongue in cheek of course. But during the Q & A one woman asked why the Japanese government hid the cars. Keeping in character, Traugott gave an answer that would make Nagatani proud. I guess the pun of the story didn’t connect with the woman. But I can’t blame her. If one is unaware of Nagatani’s work, the way in which Nagatani presented the story can catch one off guard.

I suppose that’s what makes Nagatani’s work so special: it surprises, catching one off guard with its wit and wisdom. With its combined humor, environmental and religious insight, and amazing technique, Nagatani is one of America’s finest photographers of magical and directed realism, pointing his camera on himself and the world to marvelous effect.

–by Brian Nixon