While many Missourians may be relieved that sex offenders are leaving the state, Kansas and other neighboring states may be struggling with the influx.

Missouri’s one-size-fits-all approach sends hundreds of sex offenders packing to Kansas, Illinois and Arkansas. Just across the state line, some find relief from the 1,000-foot residency restrictions. Others even end the shame of public registry.

That’s what sex offenders call “a fresh start in life”.

“Sex offenders do shop around,” said Paula Stitz, who runs the State Sex Offender Registry for the Arkansas Crime Information Center. “It’s been my experience and the experience of other state-level managers. I had actual telephone calls and them telling me that they are shopping around.”

Stitz has been handling offender registration for nearly two decades now, and she sees their constant migration as a challenge. “I view this as a process. Sex offenders move around all the time. That’s what they do. The challenge is to keeping up with them,” she said.

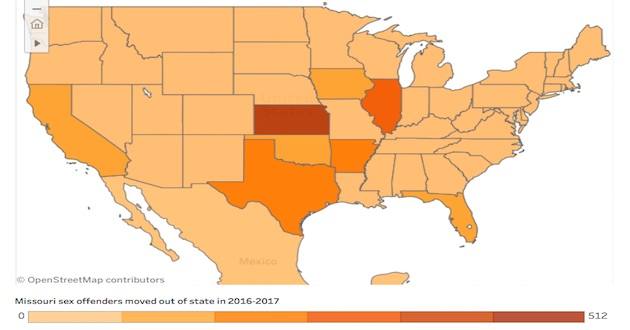

A Columbia Missourian investigation has uncovered consistent migration patterns out of Missouri by analyzing the Missouri State Highway Patrol records of more than 2,500 offenders who moved out of the state in the past two years.

Each year, Kansas, Illinois and Arkansas rank among the top three most popular destinations. Unlike Missouri, where registration is a lifetime requirement with no exceptions, each of those states uses a tiered system to determine the time convicted sex offenders spend on their registries.

Last year, during a major overhaul of its criminal statutes, Rep. Kurt Bahr, R-St. Charles, sponsored House Bill 431, which introduced a minimum registration requirement of 15 years, followed by 25 years, leaving a lifetime registration only for sexual predators who posed the highest risk.

The bill died relatively early. This year, a similar bill has passed the House and is headed for the Senate. If passed, Missouri would have the same registration tiers as Kansas.

But Kansas has something more to offer its incoming sex offenders than a tiered system. Kansas is one of at least 20 states with no sex offender residency restrictions. Aside from Colorado and Utah, another dozen of restriction-free states are mainly clustered along the East coast — from Maine to South Carolina, but the number of Missourians moving there each year are in single digits.

Kansas is now home to 512 former Missouri registrants who moved there in the past two years.

John Gauntt of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation was hesitant to admit that the absence of residency restrictions lures Missouri offenders to his home state.

“I think there is a variety of reasons,” Gauntt said diplomatically. “But I don’t know if it’s one of them. I can’t give a general answer to that. It’s really hard to say.”

Ben Trachtenberg, associate professor of law at MU, refuses to admit this makes Kansas a more dangerous place, especially for children.

“If you are the governor of Kansas, you are not especially excited that your state has become the dumping ground for the sex offenders of neighboring jurisdictions,” Trachtenberg said. “If you think that those are tremendously dangerous people, then I guess you would be worried about that for the receiving state. If you don’t, then, perhaps we should be worried for ourselves that we are mistreating people for no reason.

“If Kansas does not have a residency requirement, Illinois has 500 feet, and Missouri has a 1,000 feet, is Kansas a lot more dangerous for children than Missouri with Illinois somehow halfway in between?” Trachtenberg pondered. “I am not sure that there is any proof of that.”

Gauntt did not mention data released by the FBI listing Kansas as number eight in the states with the highest number sex offenders per capita. Arkansas is also in the top 10.

But Gauntt remains un-swayed, insisting there way of knowing for sure if an absence of residency restrictions is the primary trigger. State agencies do not question offenders when they de-register in one state and move to another.

Kansas legislators last discussed residency restrictions a decade ago, Gauntt said, but they eventually decided not put them into the statute.

“Just because we don’t have a residency requirement, the agencies are not giving the offenders a free ride,” Gauntt said. “I think the system here in Kansas has been running pretty well.”

Sex offender registration requirements in each state are different and nuanced, leaving some gray area for sex offenders to avoid certain restrictions.

Kansas offers an additional benefit for those registrants with an offense date prior to April 14, 1994, when the Kansas Offender Registration Act was enacted. Their registration doesn’t show up on the public website at all.

Of the 512 Missouri offenders who moved to Kansas in the past two years, 101 qualify for a true combo deal: No residency restrictions unless on probation or parole, plus, none of their crime records show up on the public web.

Twenty of them have rape convictions, some involving minors as young as 8 years old.

“Well, the Sheriff’s Department knows where they are,” Gauntt said.

It’s really up to law enforcement to know where those offenders reside. The state’s community notification program, which residents can sign up for, would still only include information on those appearing on the public web, Gauntt said.

Looming hope

Arkansas saw 205 Missouri sex offenders headed down south in the past two years.

“It’s not unusual,” Stitz said. Along with registrants flocking in from Texas and Oklahoma, she said, they see a lot coming in from Missouri.

According to Stitz, Arkansas has nearly 16,000 registered sex offenders, but the Arkansas Crime Information Center, which maintains the state database, publicly displays only two-thirds of them, more than 10,000 offenders — primarily those who have been assessed as high-risk offenders.

They are also the ones living under 2,000-foot residency restrictions — away from schools and day care centers. Unlike Missouri, Arkansas residential information is not as detailed, going only up to a block level.

“I think legislators’ thinking in that was that if the public knows where the exact address is, there would be some type of harassment,” Stitz said.

Incoming offenders undergo an extensive criminal background check and psychological testing, which takes up “pretty much a full day,” Stitz said.

“A conviction plays a role,” she said. “What becomes important is what comes out on that psychological test.”

For whatever it’s worth, there is always a chance to get re-assessed differently — one way or the other.

“There is always that possibility that we are going to differ from the other state that they came from. Because everybody’s assessment process is different,” she added.

Once they move to Arkansas, they begin living by that state’s rules. State law grants low- and moderate-risk offenders freedom from residency restrictions and community oversight in the form of an exemption from public registration. Certain offenders, excluding “sexually violent predators” and any of those convicted of an aggravated offense, can petition to the court after serving a minimum of 15 years on the registry.

It’s up to the court to pardon or not. Chances could be slim.

“It will be up to the assessment process and up to the court once they look at it,” Stitz said.

–First reported in the Columbia-Missourian