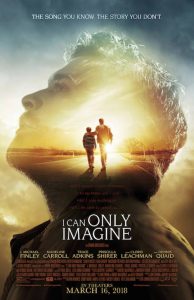

‘I Can Only Imagine’ a ‘leap forward’ from previous films, director Jon Erwin says

The same filmmakers behind Woodlawn, Mom’s Night Out and October Baby are set to release their next film in just a few days – and director Jon Erwin believes it might be their best one yet.

I Can Only Imagine (PG) debut in theaters March 16, telling the story behind one of the most popular songs in the history of Christian contemporary music. The film follows the life of MercyMe lead singer Bart Millard, who grew up in a home with an abusive father but then watched his dad come to Christ later in life.

Erwin calls the film a “leap forward” for he and his co-director brother, Andrew.

The Metro Voice recently spoke with Erin about the film. Following is a transcript, edited for clarity:

The Metro Voice: Give us a preview of I Can Only Imagine.

Jon Erwin: What an amazing story. I always claim the words of George Lucas, who said films are never complete; they’re only abandoned. Films are full of mistakes, but we’re trying to make them better and better every time. In my opinion, I Can Only Imagine is a leap forward for us. It’s an incredible true story behind the best-selling, most-played Christian song of all time. We all love the song, but no one knows the story behind the song. I remember when I was talking to (MercyMe’s) Bart (Millard), and we were kicking around the idea of doing it as a movie, I just said: “Hey, Bart, if I put a gun to your head and said, ‘Is God real?,’ what would you say?” He said “absolutely.” And he said, “(It’s) because of the change I saw in my dad. I saw a monster transform into my best friend and the man I wanted to become. There’s no other explanation for it.” Bart’s dad, in the fourth quarter of his life, became a Christian, and his dying wish was to reconcile with his son. It was that reconciliation that inspired a song that has brought hope to millions.

The Metro Voice: How can Christians and churches use this, and what type of message should they be expecting?

Erwin: What we’re passionate about is giving churches, pastors, youth groups, moms and dads, tools to engage this culture and this generation. If you can tell the right story in the right way emotionally, it stops people in their tracks and they say, “Man, I want what’s in that movie.” With Woodlawn, we’ve seen tens of thousands of decisions for Christ … mostly young people. And many say, “Can someone explain to me what’s in that movie?” A movie can be an incredible tool of instigation. We’re building on that with I Can Only Imagine. … It’s a way for churches to engage their community at a neutral site. If you study frequent moviegoers that buy the majority of movie tickets and you study the generation leaving the church today, it’s the same group of people. This is where they are. And you can talk about it afterwards. The local church is the hope of the world, and I want to support pastors in their work. We give them cultural tools.

Check out our DVD list for this month!

The Metro Voice: You have talked about how Christians need to think differently about Christian films and films in general. What do you mean by that?

Erwin: Entertainment is American’s second largest export. It’s seen all over the world. And a story that is well told is an incredible tool to communicate with people. The problem with the phrase “Christian film” is that it implies that the film is only for Christians. And I think we should think differently and begin to think about how to use film as a way for Christians to engage people in their communities, in their town, in their church. Jesus told stories, and He told stories that people could relate to. And He told those stories to explain God to people. So, I think that we should think bigger when it comes to what we can accomplish through faith-based film. Maybe it can be a tool for Christians to engage non-Christians in their world through a well-told story, instead of something to disconnect from culture. I think that we’re just scratching the surface of what Christian films can be. We’ve seen great results, but we’ve only just scratched the surface.

By Michael Foust