For nine weeks, Zyrie Berry-Henricks has been meeting with four other University of Kansas students to try to answer the question: What does it mean to be a man?

It’s part of KU’s Men’s Action Project, a 10-week program where male students discuss masculinity — both healthy and toxic.

For Hendricks, the program gives him a chance to have a conversation with other men about masculinity beyond the don’t-be-a-jerk lesson.

“We’re past the basics,” Hendricks said. “We’re now in the conversation about how to be good. How to be beneficial. How to be positive, especially when it comes to how you portray and express your masculinity.”

The #MeToo movement highlights the experiences women endure: Assaults. Harassment. Manipulation. That’s also led to a spotlight on the men responsible for that behavior, prompting new talk about what it means to be a man today and on college campuses.

Many feminists welcome the conversation. Many conservatives warn that manhood itself is under attack.

Students at KU find themselves divided, even conflicted. Some are eager for the university to do more. Others see a loaded topic with opponents more interested in shouting and quick to call out misogyny in the slightest variance from feminist dogma.

“I don’t see any men angry about it as much as they are afraid,” said Joey Pogue, a professor who researches gender at Pittsburg State University. “It’s such a contentious issue that it’s very difficult to talk about without being categorized in these black-and-white categories that are not adequate.”

For generations academic studies have focused on the accomplishments of men and often highlighted a traditional view of what makes a man. Yet masculinity hasn’t received the same attention as femininity — KU has had women’s studies classes dating back to the 1800s.

Masculinity studies received far less attention over the last two centuries, though that’s been changing. Stony Brook University in New York created its Center For The Study of Men and Masculinities in 2013. And other colleges have been offering more programs looking at manhood.

Brown University introduced an “Unlearning Toxic Masculinity” program last year. KU’s Men’s Action Project started with the school’s basketball team in 2017. That was based on a similar program from Northwestern University.

Conservative commentators see discussion of toxic masculinity as condemning of essential male traits — stoicism, competitiveness, dominance and aggression: “Stoically controlling your emotions is necessary. Competitive spirit drives success. Dominance – and the mental and physical strength required to dominate – is far superior to a lack of strength, which results in being dominated by someone else. And aggression is a means to an end. Without aggressive action, you will likely be on the receiving end, bowing to someone else’s aggression.”

They warn of a war on masculinity. Universities have also been accused of emasculating men.

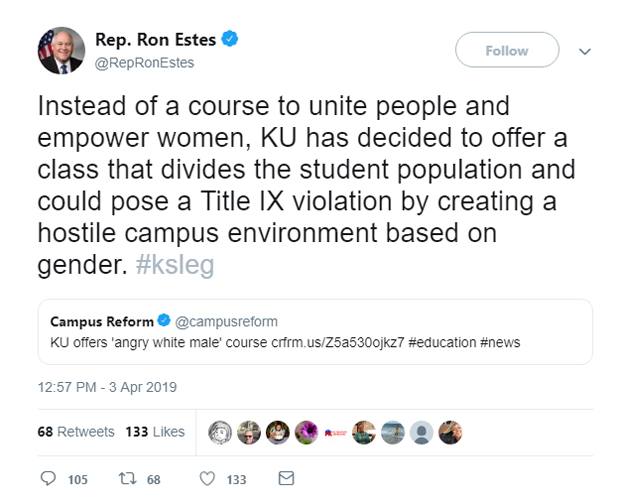

A new Angry White Males Studies course offered by KU generated its own angry backlash after being highlighted by the conservative website Campus Reform. That led Republican U.S. Rep. Ron Estes of Wichita to tweet that the class might violate Title IX regulations.

The KU community finds itself increasingly polarized over masculinity. The university says it lacks one definition of masculinity. But some believe the university pushes a singular view of masculinity on students.

“They say, ‘Oh we’re not like attacking you. This isn’t an attacking issue,’” said KU student Daniel Percival. “But at the same time, it kind of feels pushy and like they’re trying to repress an opinion or change everybody’s minds.”

Others say KU should provide more training to men — both students and faculty.

“I do feel occasionally that — not necessarily by my peers, but maybe a few of the male staff — like, I’m not taken very seriously,” said KU student Michaela Harding. “I wish the university would be teaching people to be more considerate of treating everyone equally.”

KU does require training on preventing sexual assault. There’s annual online training for all students. New students attend a workshop. Athletes must take a one-credit course on gender-based violence each year. Faculty take their own sexual harassment class online. Similar requirements are common across American campuses.

The university expanded voluntary programs focused on masculinity in recent years. A masculinity symposium at the university was recently extended into Masculinities Month. The university’s Men’s Action Project started in 2017 with the school’s basketball team. It moved onto the football team the following year. This year, it became an option for students across campus to join the 10-week discussion group.

But few people sign up. KU’s Men’s Action Project started the semester with eight students before three dropped out due to busy schedules. Kansas State University tried a similar program but didn’t draw enough students.

The schools must contend with students’ packed calendars, dozens of other campus events competing for attention and the feeling that a lecture on masculinity isn’t for them. The students whose behavior the university would most like to improve are also the most likely to pass.

“Usually, the people who show up are the people who are passionate and interested and willing to learn,” said Jamie Copaken, a Kansas City psychotherapist. “But not always the ones who need it the most.”

Realizing that, programs such as KU’s Men’s Action Project aim at men already interested in the discussion. The program hopes to turn them into role models who can reach the students the university can’t.

Universities across the country are shifting their efforts to talking with men already open to talking about masculinity.

“Oftentimes, we do spend an exuberant amount of energy trying to get the naysayers or the deniers on board when we can be spending some really great energy into people that have already bought into the idea,” said Cameron Beatty, the chair of the Coalition on Men and Masculinities with the American College Personnel Association.

The goal is still to reach the men in the middle through those students — even if that middle shrinks and men move into different camps over a university’s role in talking about masculinity.

KU student DJ Davis says the Men’s Action Project has been worth the time. Consensual sex came up during the group’s last meeting discussing dating. But that was only a starting point. The men discussed emotional manipulation, identifying their partners’ needs and their own. It made Davis realize he needs to spend more time reflecting on what he wants out of a relationship.

“What is it that I need?” Davis said. “What is it I want? And am I giving what other people want to them in those relationships? Because I don’t know. It made me think about that a lot.”

–Kansas News Service (ksnewsservice.org)

Lightning strikes Kansas airport