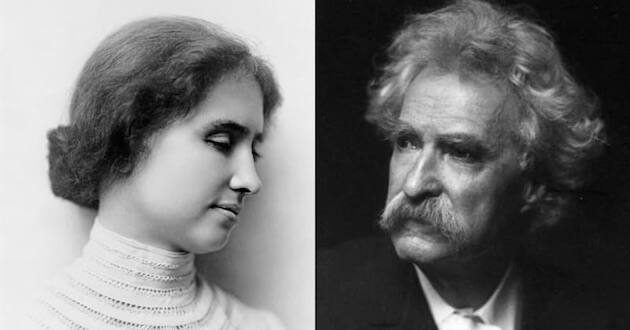

Helen Keller was 14 years old when she first met the world-famous Mark Twain in 1894. They became fast friends. He helped arrange for her to go to college at Radcliffe where she graduated in 1904, the first deaf and blind person in the world to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. She learned to read English, French, German, and Latin in braille and went on to become practically as world-famous as her dear friend, writing prolifically and lecturing across the country and around the world. Twain, with his usual understatement, called her “one of the two most remarkable people in the 19th century.” The other candidate was Napoleon.

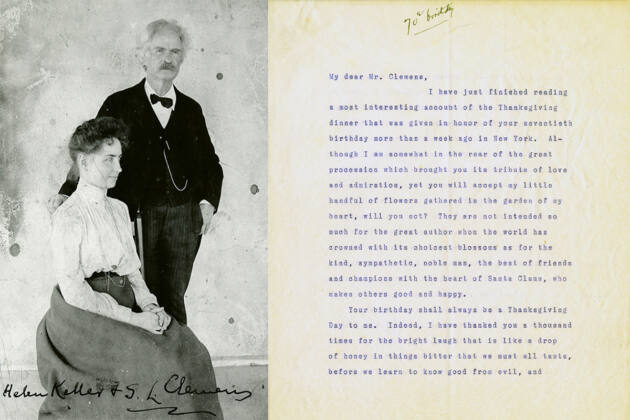

Keller lived into the 1960s and shared some of her fond memories of Twain in an autobiographical book she published in 1929. In particular, she records recollections from her last visit to her friend in his “Stormfield” home in Redding, Connecticut, which she thought of as a “land of enchantment.” She preserves for us a vivid image not only of Mark Twain—Mr. Clemens, as she called him—but of her own vivacious mind. About Twain she writes,

There are writers who belong to the history of their nation’s literature. Mark Twain is one of them. When we think of great Americans we think of him. He incorporated the age he lived in. To me he symbolizes the pioneer qualities—the large, free, unconventional, humorous point of view of men who sail new seas and blaze new trails through the wilderness.

As they gathered around the hearth one night after dinner at Stormfield, she records,

Mr. Clemens stood with his back to the fire talking to us. There he stood—our Mark Twain, our American, our humorist, the embodiment of our country. He seemed to have absorbed all America into himself. The great Mississippi River seemed forever flowing, flowing through his speech.

When Twain took her to her room to say goodnight, he said “that I would find cigars and a thermos bottle with Scotch whiskey, or Bourbon if I preferred it, in the bathroom.”

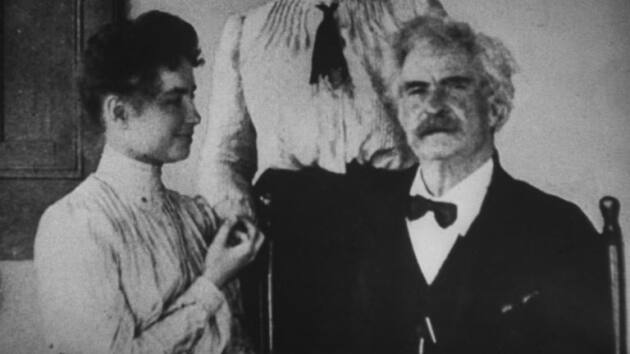

One evening, Twain offered to read to her from his short story, “Eve’s Diary.” She was delighted, and he asked, “How shall we manage it?” She said, “Oh, you will read aloud, and my teacher will spell your words into my hand.” He murmured, “I had thought you would read my lips.” And so that is what she did. Upon request, and as promised, Twain put on his “Oxford robe,” the “gorgeous scarlet robe” he had worn when Oxford University “conferred upon him the degree of Doctor of Letters.”

Here is Keller’s recollection of the evening:

Mr. Clemens sat in his great armchair, dressed in his white serge suit, the flaming scarlet robe draping his shoulders, and his white hair gleaming and glistening in the light of the lamp which shone down on his head. In one hand he held “Eve’s Diary” in a glorious red cover. In the other hand he held his pipe. . . . I sat down near him in a low chair, my elbow on the arm of his chair, so that my fingers could rest lightly on his lips.

“Everything went smoothly for a time,” Keller wrote. But Twain’s gesticulations soon began to confuse things, so “a new setting was arranged. Mrs. Macy came and sat beside me and spelled the words into my right hand, while I looked at Mr. Clemens with my left, touching his face and hands and the book, following his gestures and every changing expression.”

Keller reflected that,

To one hampered and circumscribed as I am it was a wonderful experience to have a friend like Mr. Clemens. I recall many talks with him about human affairs. He never made me feel that my opinions were worthless. . . . He knew that we do not think with eyes and ears, and that our capacity for thought is not measured by five senses. He kept me always in mind while he talked, and he treated me like a competent human being. That is why I loved him. . . . There was about him the air of one who had suffered greatly.

Whenever I touched his face his expression was sad, even when he was telling a funny story. He smiled, not with the mouth but with his mind—a gesture of the soul rather than of the face. His voice was truly wonderful. To my touch, it was deep, resonant. He had the power of modulating it so as to suggest the most delicate shades of meaning and he spoke so deliberately that I could get almost every word with my fingers on his lips. Ah, how sweet and poignant the memory of his soft slow speech playing over my listening fingers. His words seemed to take strange lovely shapes on my hands. His own hands were wonderfully mobile and changeable under the influence of emotion. It has been said that life has treated me harshly; and sometimes I have complained in my heart because many pleasures of human experience have been withheld from me, but when I recollect the treasure of friendship that has been bestowed upon me I withdraw all charges against life. If much has been denied me, much, very much has been given me. So long as the memory of certain beloved friends lives in my heart I shall say that life is good.

When Helen Keller left the enchanted land of Stormfield on that visit, she wondered if she would ever see her friend again, and she didn’t. It was 1909, and Clemens would live just one more year. But, she writes for us, “In my fingertips was graven the image of his dear face with its halo of shining white hair, and in my memory his drawling, marvelous voice will always vibrate.”

Rare film footage of Keller speaking:

The American story, still young, is already the greatest story ever written by human hands and minds. It is a story of freedom the likes of which the world has never seen. It is endlessly interesting and instructive and will continue unfolding in word and deed as long as there are Americans. The stories that I think are most important are those about what it is that makes America beautiful, what it is that makes America good and therefore worthy of love. Only in this light can we see clearly what it is that might make America better and more beautiful.

Christopher Flannery is a senior fellow of the Claremont Institute, contributing editor of the Claremont Review of Books, and host of The American Story podcast at theamericanstorypodcast.org. He is a professor emeritus of the Honors College at Azusa Pacific University, where he taught for over 30 years. He received his M.A. in International History from the London School of Economics and Political Science and his Ph.D. in Government from the Claremont Graduate School. Reprinted from Imprimis.