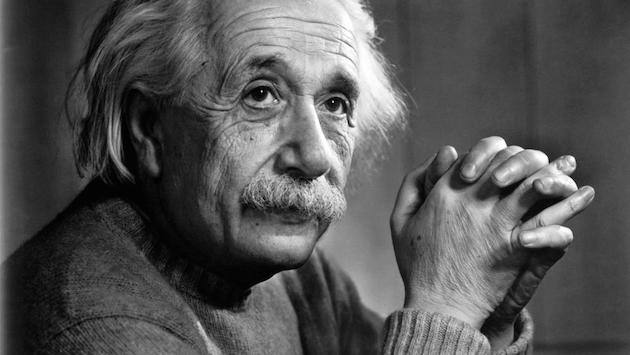

While modern atheists like to assert Albert Einstein as one of their own, recently released letters prove he was interested not only in his own faith but that of his son who converted to Christianity.

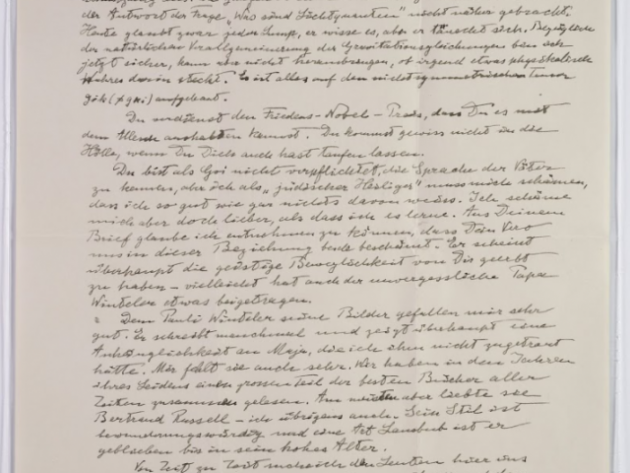

Israel’s Hebrew University has cracked open its archive on Einstein to reveal never-before-seen hand-written notes and letters penned by the famed Nobel Prize Winner.

More than 110 new manuscripts are now on display in Jerusalem at Hebrew University to mark the 140th anniversary of Einstein’s birth. Einstein was one of the founding fathers of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and is considered the most influential physicist to have ever lived.

The manuscripts, which have never been published or viewed by the public, offer new insight into the inner workings of Einstein’s mathematical mind. They also depict him as a concerned father living in the wake of Nazi Germany.

The new collection contains a hand-written appendix to Einstein’s article on Unified Theory which has not been seen since 1930. The Unified Theory was Einstein’s attempt to unify the forces of nature into one, single theory. He devoted the last 30 years of his life to this study.

The manuscripts also include dozens of pages of Einstein’s personal research notes. However, the scientific context of these notes is unknown.

The most intimate manuscript, however, is a letter Einstein wrote to his son Hans Albert in 1935 warning him of the rise of Nazi Germany. Hans was living in Switzerland at the time.

“I read with some apprehension that there is quite a movement in Switzerland, instigated by the German bandits,” Einstein wrote. “But I believe that even in Germany things are slowly starting to change. Let’s just hope we won’t have a Europe war first…the rest of Europe is now starting to finally take the thing seriously, especially the British. If they would have come down hard a year and a half ago, it would have been better and easier.”

Einstein escaped Berlin in 1922 after anti-Semitic threats to his safety.

Einstein had also expressed his reservation about the Nazi party years earlier, when he wrote a letter in August 1922 to his younger sister, Maja.

“Out here (northern Germany), nobody knows where I am, and I’m believed to be away on a trip,” Einstein wrote. “Here are brewing economically and politically dark times, so I’m happy to be able to get away from everything.”

The collection includes other letters Einstein exchanged with his friend and fellow scientist, Michele Besso about the theories he was working on.

One letter to Besso referenced Einstein’s proud Jewish faith and identity.

He jokingly teased Besso, who was born into an Italian-Jewish family, for converting to Christianity, saying, “You will certainly not go to hell, even if you had yourself baptized.”

Einstein was impressed that Besso was learning Hebrew and joked about not knowing the language himself.

“As a goy (non-Jew), you are not obliged to learn the language of our fathers, whilst I as a ‘Jewish saint’ must feel ashamed at the fact that I know next to nothing of it. But I prefer to feel ashamed than to learn it,” Einstein wrote to Besso.

To date, Hebrew University’s Albert Einstein Archives holds more than 80,000 items, including manuscripts, correspondences, photographs, diplomas and medals.

The new collection was acquired thanks to a philanthropic gift by the Crown-Goodman Family Foundation in Chicago. They were purchased from a private collector in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

The Archives’ Academic Director Professor Hanoch Gutfreund shared, “We at the Hebrew University are proud to serve as the eternal home for Albert Einstein’s intellectual legacy, as was his wish.”