Could places of worship ease the burden of schools looking to reopen while giving students space to social distance? Working with churches might not be such an outlandish suggestion.

With space at a premium and places of worship still empty amid concerns of coronavirus spread, some education experts are actively promoting the idea. In New Haven, Connecticut, church leaders have already offered to give up their space to students looking for a place to take online classes.

Concern by those determined to keep church and state separate has meant that the use of “religious spaces” for education has shrunk over the last couple of centuries, resulting in secular school systems becoming the standard for most countries.

But having spent 40 years studying the history of Christian churches and their social outreach, I know there has never been a time in the history of Christianity – indeed the history of all major religions – when religious space was not used for educational purposes.

Church schools

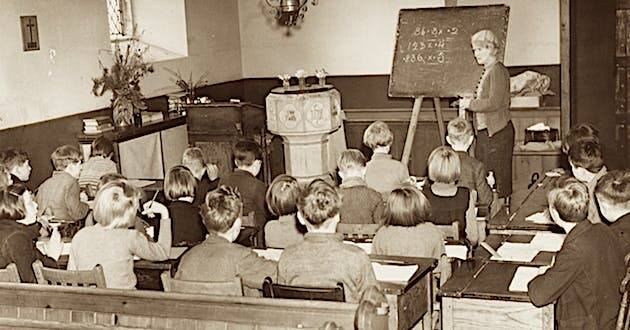

In the Europe that emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, most formal education took place inside religious spaces. Training of boys to read scriptures was a task typically performed in churches by bishops and their assistants.

The first institutions of learning in the Western Christian tradition were cathedral schools. During the day, the back pews were filled with the best and brightest schoolboys being taught the intellectual skills needed by priests.

READ: British study finds schools can safely reopen with little chance of transmission of Covid

Later, during the 10th century, Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, gave structure to the classes by mandating that a “scholasticus” – or master teacher – be appointed at cathedral schools. By the 12th century, the practice began of establishing corps of priests who lived at the cathedral and spent their days teaching.

These priests – called chapters of canons – established endowed chairs for teachers of different types of specialized knowledge. Chairs were filled by the most famous teachers or professors of the day, including the eminent philosophers Abelard and Albertus Magnus as well as Albertus’ even more famous student Thomas Aquinas, the highly influential 13th-century theologian. Chapters of canons also appointed one of their members as a “dean” to supervise all the different courses of study – a term still employed by universities.

Christ Church College, Oxford, serves as a cathedral and a seat of learning. Photo by © Fine Art Photographic Library/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The birth of universities

Eventually the most successful cathedral schools drew too many students to be taught inside the churches themselves. By the 13th century, cathedral schools gave way on one side to grammar schools, which taught Latin, and on the other to universities – where students paid money to listen to the lectures of professors and received degrees based upon their displayed knowledge. The lecture halls in which these university students were taught became the forerunners of modern classroom buildings.

Education in early modern Europe increasingly left the pews behind as the focus expanded beyond teaching future clergy. The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century rejected the notion of a priesthood and demanded that everyone learn to read the Bible, preferably while they were young.

To enable this, schools dedicated to teaching boys and girls who would not enter the clergy were established, increasingly in buildings distinct from places of worship.

Because Protestants made the church a department of the state, such schools were maintained by the country’s ruler but staffed by the church. Soon Catholics followed a similar practice of building church schools for teaching boys and girls not destined for a religious vocation. The Jesuit religious order, founded in the 16th century, dedicated itself to education and pioneered the building of residential campuses for their schools that were distinct and autonomous from local churches.

Toward public schools

But it was the French Revolution that sped up the movement toward secular schooling as the cultural norm. Revolutionaries in France and other European states argued that the nation deserved the loyalties previously claimed by the churches. As such, churches should be shut down to stop patriots from being distracted from a greater loyalty to the nation.

Revolutionaries failed in their efforts to deprive church schools of their status, however. Later nationalists, in reflecting upon why revolutionaries had failed, concluded that the education offered in church schools, rich in centuries of practice, was simply too strong for secular schooling to challenge.

So they pushed for redirection of state subsidies away from church schools to secular education. By the end of the 19th century, such initiatives had resulted in the secular public school systems in operation today.

Churches, schools and state

Church schools did not disappear, however. In Western societies, some parochial schools and private faith-based schools continued to flourish. And there is even precedent for schools using churches in times of crisis, such as to accommodate children evacuated from major cities in the U.K. during World War II.

Meanwhile, outside of Western societies, church schools became a major tool that Christian missionaries used to educate indigenous peoples. European colonial governments came to subsidize mission schools as cheap alternatives to building state school systems. In many African and Asian states today, church schools subsidized by foreign missions still educate significant numbers of students.

The constitutions of most modern states maintain a strict separation between church and state. And there are rules in place in countries with secular school systems that protect the primacy of secular schooling over all other types of schooling.

Courts have also moved to protect the rights of students with minority religious backgrounds from persecution no matter what schools they attend.

Education in the West has been progressively outgrowing the church environment for centuries, yet education in religious settings continues to lead students back toward faith. Students educated in religious settings also continue to outperform secular counterparts in testing at all levels.

Whatever the impetus for using churches for as a setting for schools, awareness of this capacity of religious space will likely remain a concern for promoters of the separation of church and state – even in these unprecedented times of pandemic.

– Andrew Barnes | Professor of History and Religious Studies, Arizona State University