As early voting is already underway for Tuesday’s stadium tax vote, promises by proponents are being questioned. More business, more fans, more revenue, and even a pennant-winning team are now the lure.

The cost, about $2 billion for the works, hotels, restaurants, clubhouses, and stores, is being bandied about like a hot potato between the owners, city, county, state, and others, all while the history of the St. Louis Rams football stadium is fresh at hand in the mind of the Missouri Legislature.

Perhaps a brief overview of the history of baseball stadiums in Kansas City would be beneficial.

First, there are many professional baseball teams with downtown stadiums, including in Detroit, New York, Boston, St. Louis, and other locations, many of which are historical structures.

Boston’s stadium was built in 1912; Busch Stadium, on the other hand, was rebuilt in 2006. Detroit built Tiger Stadium in 1912, but Comerica Stadium replaced it in 2000.

Cleveland Municipal Stadium, where the Cleveland Indians played before 1994, was built in 1931, before the Indians moved to Jacobs Field.

The cost of building Jacobs Field was $175 million, with $84 million provided by Cleveland taxpayers and $91 million provided by Indians owner Richard Jacobs.

In 2008, the naming rights were sold to Cleveland-based Progressive Insurance for an annual cost of $3.6 million per year. In the stadium’s opening year, attendance averaged 39,121 fans.

I focus on Cleveland because John Sherman, the majority owner of the Royals, was Vice Chairman of the Cleveland Indians/Guardians before buying a majority share of the Kansas City Royals, and it is his group that is proposing a downtown ballpark.

Kansas City has had its share of baseball teams and stadiums.

The original stadium was built for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1923, where they played from 1923 to 1931, and for the Kansas City Blues, a minor league team. For a while, it also served as a home for the Kansas City Athletics, the Kansas City Spurs soccer team, the Kansas City Royals, and the Kansas City Chiefs football team.

Originally, it was known as Muehlbach Field from 1923 to 1937, Rupert Stadium from 1937 to 1943, and Blues Stadium from 1943 to 1954.

Initially, it accommodated 17,476 people on a single level, which grew to 30,296 from 1955 to 1961, 34,165 from 1961 to 1969, 34,164 from 1969 to 1971, and 35,561 during its final two years of operation, 1971 and 1972. The original construction cost was $400,000.

The municipal stadium was integrated between 1923 and 1955, hosting the minor league Kansas City Blues of the American Association and the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues.

When the Philadelphia Athletics relocated to Kansas City in 1955 to become the Kansas City Athletics, they almost completely rebuilt the stadium.

Showing my age, I remember going to see the athletes. Once, I was invited to lunch at the family bank along with players from the Angels and the Twins, and on one occasion, my grandfather took me to the game along with his guest, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Earl Warren. At the time, I was too young to even think of quizzing him on cases. We had great company, and my hero at the time was a player, Bill Tuttle.

Much of the history of stadiums centers around the illustrious owners of the teams. Arnold Johnson was responsible for moving the Athletics from Philadelphia and the Blues, a Yankee farm team, to Denver. Initially, the plan was for him to spend a few years in Kansas City before relocating to Los Angeles. However, in 1955, the Athletics drew 1,393,054 in attendance, the third highest in baseball, and the Athletics found a home.

In 1960, following Johnson’s death, Charles O. Finley bought a controlling interest in the team. He brought a lot of changes: Harvey, the baseball-providing rabbit behind home plate, and new colors, green and gold. He invested $400,000 of his personal funds to renovate the stadium, for which the city reimbursed him $300,000.

The lease between Charlie and Kansas City honored his desire to keep the team in Kansas City, right up to the time he executed an escape clause in the document, and in 1968, the team moved to Oakland.

Fortunately, Kansas City earned an expansion team in 1969, the Royals, a name that had nothing to do with the Monarchs’ history but had everything to do with the American Royal. It also had everything to do with the owner, Ewing Kauffman, who instituted a complete player development system that resulted in two World Series wins.

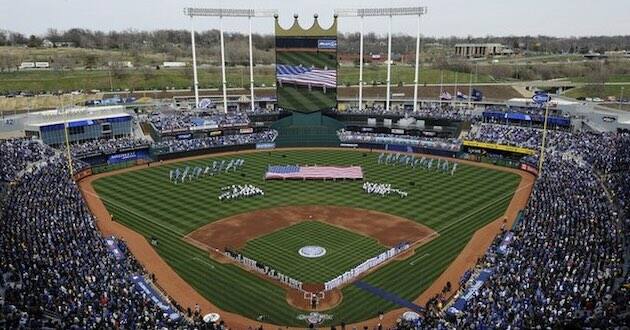

In 1973, Kauffman Stadium opened in Kansas City at the intersection of I-435 and I-70, acknowledging the dispersed fan base of both the Royals and Chiefs across numerous states and counties.

I can remember catching the Royals on radio from Chanute, Kansas, and later in Colorado, before Colorado had its own team, the Rockies. The joint stadiums not only allowed for access but also shared parking and other amenities. Kauffman Stadium initially had seats for 40,793.

Ewing Kauffman died in 1993, and his estate maintained ownership until 2000, when David Glass bought them.

In 2007, Royals Stadium was refurbished. The seating capacity was lowered to 37,903, and the cost of renovating the stadium, which was $250 million, was borne by Jackson County, Missouri residents, and Royals management. As a result, Jackson County residents were given a preference for Royals tickets.

In 2020, the majority ownership of the Royals was sold to John Sherman, with a host of Kansas Citians as minor owners.

In 2022, John Sherman, in an open letter, called for a downtown ballpark for the Royals.

Despite the current lease on the Royals’ Stadium running until 2031, the Royals have proposed a $2 billion expenditure, a mixture of public and private funds, that will supposedly create 20,000 jobs and an estimated $2.8 billion in economic output.

Like many, I question the numbers, site selection, and secondary expenses, like infrastructure. I also question whether a different location can spur a team to winning seasons. There are a great many unknowns: the cost of real estate, the displacement of people and businesses, the destruction of historic structures, and even the sources of funding for the project.

I am reminded of the T-Mobile Center and the words of Mayor Barnes in 2007, “If we build it, they will come,” meaning a professional basketball or hockey franchise. We’re still waiting on that team.

I am reminded of Charles O. Finley, who promised to keep baseball in Kansas City. I am reminded of why we needed a new airport, promised not to be funded by public tax sources but with no improvement in infrastructure getting to and from it. Perhaps a great deal will depend on the city itself.

Unlike Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, or LA, our Royals belong to the counties, cities, and states surrounding Kansas City and Jackson County, as well as Kansas City. During a period when numerous baseball teams are experiencing a decline in fan base, I seek additional answers to unasked questions.

An early location was near the Kansas City Star building, another tax mess that Kansas City would rather forget. After receiving a tax abatement, McClatchy, the owner of the Kansas City Star, transitioned to private ownership, being acquired by Chatham Asset Management, and the building was vacated by the Star in 2021. The building is now owned by the Privatera family, who are inclined to sell it to the Royals.

The Jackson County Legislature, mindful of the consequences of every political move, voted 8 to 1 in January to extend the current 3/8% sales tax for 40 years, dividing it equally between the Chiefs and Royals.

The only questions remaining are whether Jackson Countians will vote to continue the sales tax or believe it’s a $2 billion trick play.

–Robert White is a local historian and writer. His other columns can be enjoyed HERE.