History had a lot to do with where Black neighborhoods were created on both the Missouri and Kansas side of the state line.

Many of these neighborhoods were already established by the time the first Juneteenth commemoration occurred in 1866. Much of the slave trade was along the rivers, so before and during the Civil War, Black neighborhoods sprung up in the East and West Bottoms, and Kansas, being a free state, became a haven for Blacks escaping enslavement. The areas expanded after the Civil War, as Blacks came to the area for employment on the bridges, railroads, and agriculture as Kansas City grew into an important commercial center.

Kansas City has a rich heritage of ethnic backgrounds, but Kansas City has also had a history of destroying much of the Black heritage through highway construction, stadium construction, and urban renewal, leaving many of the neighborhoods broken up and piecemeal.

Previously but there were Black neighborhoods on both sides of the state line, in both Missouri and Kansas. The 18th and Vine District with it BarBQ, Jazz, and Negro League Baseball Museum is well known, but there are other areas around Kansas City that have also contributed to the ethnic culture, which was kept separate from White culture for over 100 years.

READ: Original Juneteenth was a spiritual event

With the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, it became illegal to discriminate in the terms, conditions, or privileges of sale or dwelling because of race or national origin. It was the culmination of the Rumford Fair Housing Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1963 and 1964, all attempting to end years of the concept of “separate but equal” in housing.

The term redlining, separate but equal, was perfectly legal before these laws passed, but the policy locked cultures, people, and centers of influence behind hard borders based on nothing more than colors and perception.

Missouri was one of the last states to desegregate in terms of redlining, the restrictions to lending in specific area based on race, income, or other factors, which kept separate but equal alive longer than in other parts of the country.

Separate but equal, of course, was anything but equal, but it allowed Black culture to develop without the influence of other cultures. European cultures were assimilated while Black culture was kept separate. The Black Community even had its own newspaper–the Kansas City Call–that began in 1919.

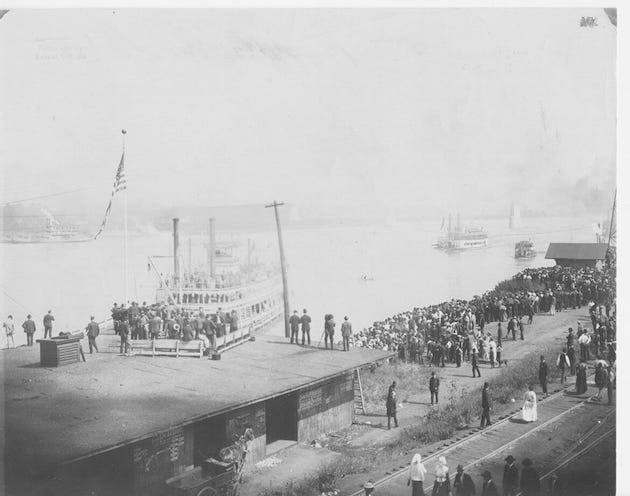

At the foot of Kansas City’s Main Street, crowds gather for the arrival of a steamboat. (Missouri Valley Special Collections | Kansas City Public Library)

In the historic Westport District, the Steptoe Neighborhood was an area of neat clapboard housing that encompassed the eastern area of the Country Club Plaza which it predated. Within that area were such locations as the Penn School, St. Luke’s African American Methodist Episcopal Church, as well as St James Baptist Church, both catering to the Black community. St Luke’s was demolished in 2003, leaving St James as the only remaining building in the Steptoe area. The expansion of the Country Club Plaza into what was the Steptoe Neighborhood was an expansion into one of the first mixed neighborhoods in Kansas City.

Troost was the dividing line for a long time in Kansas City, but the dividing line was often fluid. The economic crash of the 1890s allowed many non-affluent Blacks to own modest homes east of Paseo at 24th, which created a Black Quality Hill.

In Kansas City, much of the Black community was affected by urban renewal. The 18th and Vine area was determined by City Hall to be blighted in the 1960s, and the Watkins Freeway runs through much of what was the Black community at the time. The results are pockets of saved culture, like the Bruce R Watkins Cultural Heritage Center at 3700 Blue Parkway. After the Second World War, Kansas City had a Black Chamber of Commerce and directory, The Negro City Directory, published by Scott Directory Publishing, included a listing for Black-owned business, as well as Black individuals.

Much of the center of Black Culture in Kansas City, Missouri was anchored around the 18th and Vine area with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, American Jazz Museum, Gem Theater, the Call newspaper, the Attucks School, Paseo YMCA, and the founding locations of Kansas City Bar BQ in both Gates and Sons and Arthur Bryant’s. It expanded into the site of the Municipal Stadium, which was home to the Kansas City Monarchs, the Black team, as well as a minor league White team before integration. General Hospital #2, at 22nd and Kenwood, served Black residents and, often forgotten, the old Research Hospital at 23rd and Holmes, now present-day General Hospital, served the Black Community before desegregation.

The Freedom Trail Memorial at 751 Madison and Hells Half Acre on 8th Street in the West Bottoms highlights some of the early Black culture in Kansas City.

Across the state line in Kansas, the demarcation was the county line between Johnson and Wyandotte Counties. Most Black culture was centered in Wyandotte County. The Quindaro Township, originally a town named for Nancy Brown Guthrie whose Wyandot Indian name was Quindaro, was located on the Missouri River. As the town grew, it was occupied by more and more escaped slaves. It is part of the Kansas and Missouri Black History tour.

Also part of the tour is the Kresge’s Department Store on Minnesota Avenue. From Quidaro, the Black Community fueled at first by slavery and then employment, expanded into what is today Rattlebone Hollow and Juniper Gardens near 5th and Parallel between 1878 and 1882. In 1905, the Kansas Legislature exempted Kansas City, Kansas from a state law prohibiting racial desegregation, a forerunner to Brown versus the Board of Education. This Legally desegregated Sumner High School, a school providing some of the first Black students to the Kansas College System.

One of the last events on the tour is the Donald Sewing House in Fairway. In 1966, seeking better educational opportunities for their children, Donald and Virginia Sewing broke the color barrier of the county line, moving their family to all White Fairway, Kansas in Johnson County.

It is easy to highlight the dates, locations, and structures of segregation, but it is the culture that has been lost, the stories, achievements, and gifts from each. It is the Black culture that we celebrate with commemorations like Juneteenth and Black History Month.

–Bob White is a Kansas City-area resident and history writer for Metro Voice. Search his name on our homepage search bar for more or read his other stories HERE.