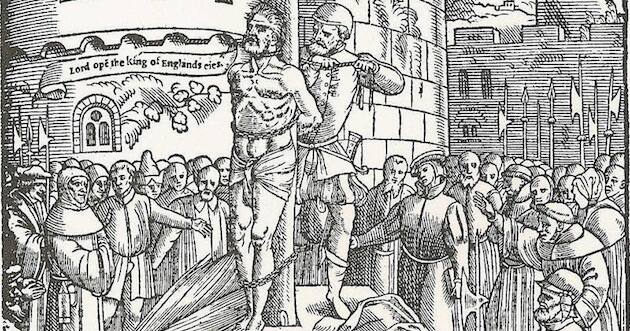

William Tyndale, “Father of the English Bible,” was burned at the state in October 1536.

How many Bibles do you have in your house? For most of us, Bibles are easily accessible, and many of us have several. That we have the Bible in English owes much to William Tyndale, sometimes called the Father of the English Bible. 90% of the King James Version of the Bible and 75% of the Revised Standard Version are from the translation of the Bible into English made by Tyndale, yet Tyndale himself was burned at the stake for his work on October 6, 1536.

Tyndale was born near the Welsh border of England in 1494. Forty years earlier, two important events occurred in Europe which would have a great impact on Tyndale’s life and work. In May 1453, the Turks had stormed Constantinople, and the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire fell to the Muslim invaders. Greek scholars fled westward and brought with them a scholarship that had been almost forgotten in the West. Greek language studies of the classics increased, and the Scriptures began to be studied in the original Greek, rather than the Latin Vulgate. The invention of the printing press in 1454 was a second important development. The printing press would eliminate copyist errors and make the Scriptures more easily available in quantity editions. But to have the Bible in English was illegal.

Back in the fourteenth century, John Wycliffe was the first to make (or at least oversee) an English translation of the Bible, but that was before the invention of the printing press and all copies had to be handwritten. Besides, the church had banned the unauthorized translation of the Bible into English in 1408.

Over one hundred years later, however, William Tyndale had a burning desire to make the Bible available to even the common people in England. After studying at Oxford and Cambridge, he joined the household of Sir John Walsh at little Sudbury Manor as tutor to the Walsh children. Walsh was a generous lord of the manor and often entertained the local clergy at his table. Tyndale often added spice to the table conversation as he was confronted with the Biblical ignorance of the priests. At one point Tyndale told a priest, “If God spares my life, ere many years pass, I will cause a boy that driveth the plow shall know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

It was a nice dream, but how was Tyndale to accomplish this when translating the Bible into English was illegal? He went to London to ask Bishop Tunstall if he could be authorized to make an English translation of the Bible, but the bishop would not grant his approval. However, Tyndale would not let the disapproval of men stop him from carrying out what seemed so obviously God’s will. With encouragement and support of some British merchants, he decided to go to Europe to complete his translation, then have it printed and smuggled back into England.

William Tyndale Follows God’s Will to Germany

Tyndale went to the Bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall, to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. Tunstall refused. But while in London Tyndale came into contact with several merchants who were smuggling into England some of Martin Luther’s writings from Germany. They encouraged Tyndale to go to Europe to translate. They would help smuggle the Bibles back into England.

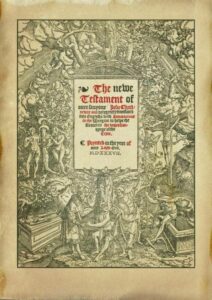

In 1524 Tyndale sailed for Germany. In Hamburg, he worked on the New Testament, and in Cologne, he found a printer who would print the work. However, news of Tyndale’s activity came to an opponent of the Reformation who had the press raided. Tyndale himself managed to escape with the pages already printed and made his way to the German city Worms where the New Testament was soon published. Six thousand copies were printed and smuggled into England. It was the first translation of the Bible from the original Greek into English –indeed, it was the first translation of a Greek book into English.

King Henry VIII, then in the throes of his divorce from Queen Katherine, offered Tyndale a safe passage to England to serve as his writer and scholar. Tyndale refused, saying he would not return until the Bible could be legally translated into English. Tyndale continued hiding among the merchants in Antwerp and began translating the Old Testament while the King’s agents searched all over England and Europe for him.

The bishops did everything they could to eradicate the Bibles — Bishop Tunstall had copies ceremoniously burned at St. Paul’s

Cathedral; the Archbishop of Canterbury bought up copies to destroy them. Tyndale used the money to print improved editions!

Tyndale’s Betrayal and Martyrdom

In 1534 Tyndale was betrayed by a false friend near Brussels, arrested by imperial forces, and thrown into prison. After a year and a half in prison, he was brought to trial for heresy — for believing, among other things, in the forgiveness of sins and that the mercy offered in the gospel was enough for salvation. He was accused of maintaining that faith alone justifies.

In August 1536, he was condemned then, on October 6, 1536, was beaten then burned at the stake. His last prayer was “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” The prayer was answered in part when three years later, in 1539, Henry VIII required every parish church in England to make a copy of the English Bible available to its parishioners.

Today, Tyndale’s first Bible translation can be read online.

–By Dan Graves

Adapted from an earlier Christian History Institute story.

Bowie, Walter Russell. Men of Fire. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1961.

Daniell, David. William Tyndale, a biography. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Dictionary of National Biography. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. London: Oxford University Press, 1921 – 1996.

Kunitz, Stanley L. British Authors Before 1800; a biographical dictionary. New York: H. W. Wilson, 1952.

Mozley, J. F. William Tyndale. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York: The Macmillan company, 1937.

Sampson, George. Concise Cambridge History of English Literature. Cambridge, 1961.

“Tyndale or Tindale, William.” The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

Wild, Laura Huld. The Romance of the English Bible; a history of the translation of the Bible into English from Wyclif to the present day. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1929.