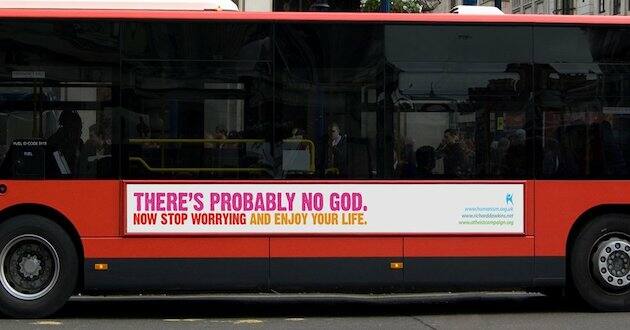

Two decades ago, Sam Harris dropped a literary bomb with “The End of Faith.” The book didn’t just get tongues wagging; it lit the fuse of the now-legendary New Atheists movement.

Harris, in his distinct drawl, dismantled religious dogma, arguing that faith-based beliefs were not just outdated but inherently dangerous. According to the Californian, religion was a primary driver of conflict, intolerance and terrorism.

A world governed by secularism and reason, he argued, was the only way forward. Religious belief, in Harris’ opinion, was incompatible with progress. This message resonated in the post-9/11 world, where the clash of civilizations narrative was gaining traction. Today, however, New Atheism has fizzled out, even as religious belief in Western nations is decreasing.

What happened?

Along with Harris, the New Atheist movement was spearheaded by Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens and Daniel Dennett. Together, they were known as the “Four Horsemen.” Each brought a unique perspective and set of skills to the movement. Harris — with his background in neuroscience and philosophy — combined empirical evidence with philosophical arguments.

READ: Former Muslim, then Atheist finds Christ

Meanwhile, Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist with a penchant for wearing quirky ties, focused on dismantling creationist claims and promoting scientific understanding. Hitchens, a journalist and polemicist with a sharp wit, brought wry humor and fiery rhetoric to the cause. A fantastic orator, Hitchens targeted organized religion with acerbic, unapologetic critiques. Dennett, a philosopher and cognitive scientist, examined the evolutionary and brain-based origins of religious belief.

Their primary obsession

The foursome was, for lack of a better description, absolutely obsessed with Islam. Specifically, they blasted it whenever the opportunity presented itself. As Peter Thiel recently pointed out, this obsession seemed to bind the New Atheists to other potential threats. Thiel noted that while they were relentless in their critique of Islam, they failed to address other significant issues, like the rise of communism in China. This monomaniacal fixation on Islam’s supposed threat to the West prevented them from having broader discussions. It limited their narrative and, ultimately, their overall appeal.

The New Atheists were, in many ways, iconoclasts. They were excellent at tearing things down but offered very little of genuine substance to replace what they sought to destroy. Calls to think “rationally” are well and good, but what does this actually mean in practice? How does one build a community, find meaning, or deal with life’s inevitable suffering with mere rationality as a guide?

The New Atheists seemed to assume that once religion was debunked, a utopia of reason and science would naturally follow. This was a naive and simplistic view of human nature and society. The level of hubris was, in retrospect, rather stunning.

They were condescending and became extremists

Moreover, and this is a vitally important point, there was a sheer arrogance in the way New Atheists approached almost every debate. They regularly came across as condescending and haughty, dismissing believers as ignorant or deluded. Ironically, in their assertions, they became extremists in their own right. How can anyone say, with complete conviction, that God does not exist? Sure, God may not exist, but claiming to know this with absolute certainty is intellectually dishonest. This attitude alienated many who might have been initially sympathetic to their cause.

Today, Pascal’s wager still holds a lot of wisdom. It suggests that believing in God, even if His existence is uncertain, is a safer bet than not believing. If God exists and you believe, you gain everything; if He doesn’t, you lose nothing. This approach, often dismissed by atheists as delusional yet seen by others as pragmatic, underscores a critical flaw in the four men’s argument. Their movement’s downfall, I suggest, stemmed from an inability to recognize the limits of human knowledge and the complexities of belief.

It became a clique

What began with the noble aim of promoting critical thinking gradually devolved into an intellectually arrogant clique. From their high tower of so-called sanity, they began to preach down to the masses, laughing at the “dumb fools” who believed in a supreme being. What started as a thought-provoking movement turned into a jock-like boys’ club, punching down at those they deemed less enlightened. This intellectual elitism alienated many potential allies and fostered a perception of atheism as a club for the smug and self-satisfied.

Ultimately, the New Atheists failed because they underestimated the human need for meaning. Religion, for all its faults, provides a framework for understanding the world, a sense of community and a way to cope with life’s challenges. By dismissing religion entirely, the New Atheists offered nothing to fill the void. Rationality and science are, of course, crucial, but they don’t address the existential questions that religion grapples with — and they never will.

John Mac Ghlionn is a researcher and essayist. He covers psychology and social relations. His writing has appeared in places including UnHerd, The US Sun and The Spectator World.

Reprinted from ReligionUnplugged with permission.

Photo usage rights: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/