What’s Old Is New Again: Kansas City’s Streetcars

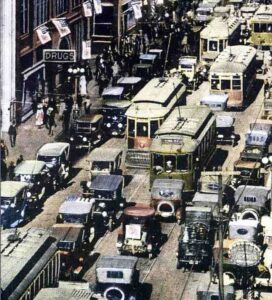

Not many towns or cities around the world have eliminated streetcars, only to bring them back 60 years later. For many communities, streetcars have long been seen as a status symbol. Mining towns like Cripple Creek, Colorado, and Butte, Montana, saw them as a sign of having “made it.” But in each case, once the ore ran out, the economy shrank, or new means of transportation emerged, streetcars were among the first things to go. Kansas City ended its streetcar service in 1957.

Kansas City has always had a reputation for strong public transportation. At one point, it boasted the third-largest cable car system in the United States, behind only San Francisco and Chicago. The earliest lines were mule-drawn, running from Westport to downtown as early as 1870—less than a decade after the Civil War. The city’s cable car era ended in 1912, by which time ridership had reached nearly 120 million per year. In 1922, counting only revenue riders, that figure peaked at 136 million. It wasn’t until 1942, during World War II, that this number was surpassed, reaching 153 million riders, mainly due to gas rationing. In 1926, the Kansas City Public Service Company took over management of local transportation and began substituting streetcars with buses to save money.

By 1955, the Kansas City Public Service Company opted to sell its last 161 streetcars and their overhead wires to European countries that used the same gauge tracks. The final cars were sold off in 1957, as diesel buses proved more economical than continued streetcar operations. At its height, Kansas City had 25 separate streetcar routes and 700 cars, all privately owned before being acquired by the Public Service Company.

The Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) was formed via a bi-state compact signed on December 28, 1965, absorbing the Public Service Company and expanding bus service into Wyandotte and Johnson counties in Kansas—thus ending the streetcar era. Tracks and rights-of-way were paved over, dug up, or sometimes sold.

The economics that once favored cars and buses were soon challenged by rising oil, labor, and machinery costs. Buses from the 1950s began to need more work. Concerns about pollution also grew. Starting in the late 1960s, the pressure to run cleaner meant gasoline and diesel became more expensive options. Subways and elevated trains in some cities revived interest in streetcars and mass transit, but the biggest obstacle was the cost of installing new infrastructure. Cities like Orange County, Charlotte, Dallas, Columbus, Tampa, Milwaukee, Spokane, Philadelphia, and Kansas City all considered or launched new streetcar ideas.

In Kansas City, a Virginia-based light rail activist began pushing for a system in 2009, and by 2012, finally gathered enough votes. A sales tax was approved, but not enough to cover a high-speed line from Union Station to Kansas City International Airport. Kansas City broke ground on the modern trolley in May 2014 and it opened in May 2016. The initial 2.2-mile project, funded by a $102 million ballot initiative, ran from Union Station to City Market. In October 2025, a 3.5-mile extension took the line to UMKC, with further expansion north to the Missouri River set for completion in 2026. As of February 2025, the free-to-ride trolley (designated Ride KC route 601) has logged 15 million rides.

Whether modern streetcars are economically viable remains up for debate. All sorts of train projects, including Amtrak to high-speed rail, are under scrutiny, and many high-speed rail proposals have been scrapped. Heavy rail projects in California and Texas have lost funding, while light rail is seeing modest growth. According to federal data, Kansas City’s recent extension is the most expensive to date: $351.7 million for 3.5 miles—over $100 million per mile, far exceeding the previous records of $27.8 million in Salt Lake and $54.5 million in Detroit. The Kansas City extension relied on a $174 million Federal Transit grant. The remainder is intended to come from a voter-approved Transportation Development District and property value increases within the district, but the project also ran $35 million over budget.

Other complications follow. During COVID, Kansas City subsidized bus fares at levels that seemed bottomless. Recently, the city finished a new airport terminal funded by the airlines, not taxpayers. But post-pandemic, city finances have tightened. Now, many residents, used to free streetcar rides, must pay for the bus, and absorb the costs of maintenance, staffing, and fuel.

You tend to meet the best people in Kansas City transportation.

––Bob White is a published author and lives in Pleasant Hill. He regularly writes about history for Metro Voice.

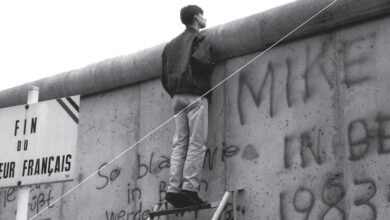

Main Image: Jason Doss, WikiCommons 2.0