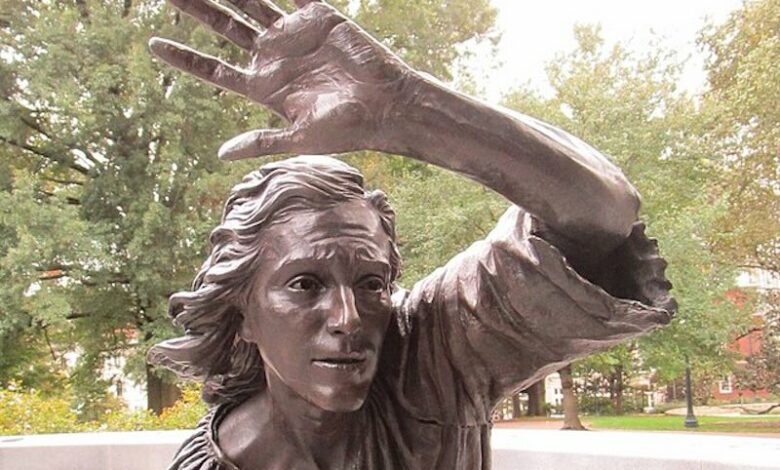

The Incredible Journey of Mary Draper Ingles on the American frontier

Life was cheap on the American frontier during the French and Indian War.

In mid-summer of 1755—the exact date is uncertain—a band of about 16 Shawnee attacked the settlement of Draper’s Meadows, located near today’s Blacksburg, Virginia. They killed at least four people of the settlement, including Col. James Patton, a giant of a man who died sword in hand after slaying two of the attackers.

The Shawnee took five people captive, among whom were 23-year-old Mary Draper Ingles and her two sons, Thomas, age 4, and George, age 2. William Ingles, Mary’s husband, was one of those who evaded capture. After looting and setting fire to some of the cabins, the raiders took their prisoners and began a month-long journey along rivers and through mountain passes to Shawneetown in present-day Ohio.

Three months later, in a rare act of courage, a desperate Mary Ingles escaped her captors and headed back through the wilderness to Virginia.

Life Among the Shawnee

Like so much of the history of America’s colonial days, accounts vary in the details of Mary Ingles’s escape from the Shawnee and her 42-day odyssey back to her husband and Southwest Virginia. James Alexander Thom’s best-selling novel, “Follow the River,” is a gripping read and has been praised for its attempts at historical accuracy. John Ingles, who was born after Mary rejoined her husband, left us a written record of his parents’ lives based on the stories they’d shared with him.

Here, with its eccentric misspellings and punctuation, is his description of what occurred when the captives reached what he calls “the nation”:

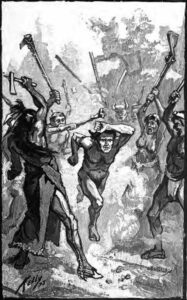

“The next day after they got to the nation the prisoners had to undergo the Indian custom of running the gauntlett which was purformed by forming a two lines of all the Indians in the nation men women and children and the prisoners to start at the Head of the two rows formed & run down between the lines & every Indian giving them a cut or a pelt with switch sticks or such things as they could provide which was a very severe opperation and espitialy on my Aunt Draper whose arme had not got near well from the wound she had received when she was taken prisoner.”

Inexplicably, Mary Ingles was spared this ceremony of mockery and pain. When she demonstrated her abilities as a seamstress, she was put to work making shirts from cloth sold to the Shawnee by French traders. After a few weeks, the Shawnee packed up and headed to a salt lick in what is now Kentucky. Forced to accompany them to help make salt and giving up all hope of reuniting with her boys, Ingles decided she “wood leave them & try to get Home or dy in the woods.”

After convincing another prisoner, an older “Dutch woman” who was possibly a German immigrant, to join in her escape, the two women laid their plans. They decided to wear only the clothing they had on to avoid rousing suspicion and carried with them one blanket apiece, two tomahawks, and perhaps a knife. Perhaps believing that the forbidding forests and rugged terrain that extended hundreds of miles acted as a prison, the Shawnee paid them little attention as they left the camp, supposedly in search of grapes.

The Long Walk Across the American Frontier

Now began an ordeal that beggars the imagination.

The women left the camp in mid-October, which meant dealing with weather that would only grow colder. By November, they were contending with snow and icy creeks. They ate whatever they could find: corn in an abandoned cabin, part of an animal carcass left behind by an Indian, and the random offerings of nature. At times, they were reduced to eating roots. They were prey to man and beast as well, and on several occasions had close encounters with Indians but were never discovered.

The women left the camp in mid-October, which meant dealing with weather that would only grow colder. By November, they were contending with snow and icy creeks. They ate whatever they could find: corn in an abandoned cabin, part of an animal carcass left behind by an Indian, and the random offerings of nature. At times, they were reduced to eating roots. They were prey to man and beast as well, and on several occasions had close encounters with Indians but were never discovered.

On they walked, 10 to 20 miles per day, following the rivers east and south toward Virginia and safety.

After a time—again, no exact date is available—the Dutch woman drifted toward insanity brought on by fear and hunger. According to John Ingles’ account, this woman “disheartened & discouraged got very ill natured to my mother & made some attempts to kill her blaiming my mother for perswaiding her away & that they wood dye in the woods and as she was a good deal stouter & stronger than my mother she used every means to try to please the old woman.”

READ: The hidden spiritual advice on the Franklin cent

When they were about 50 miles from “where my mother was taken prisoner,” the older woman made a second and more serious attempt to murder Ingles. After a struggle, the younger woman broke away, fled, and left her murderous and half-mad fellow traveler behind.

Rescue and Afterwards

After walking some 500 miles, nearly naked and close to death from exposure and starvation, Ingles reached Draper’s Meadows, where Adam Harmon and his two sons, whom she knew, heard her cries for help, took her to their cabin, and warmed and fed her. Soon her husband joined her. The Dutch woman survived as well, and after her recovery she apparently returned to her home colony of Pennsylvania.

While Mary Ingles never again saw her younger son—George probably died shortly after being separated from her—Thomas, by now age 17, was found. A ransom paid to the Shawnee returned him to his family, where he had to relearn the ways of his people and to speak English again. Despite her many hardships, Mary and William Ingles had four more children. She lived to the ripe old age of 83.

In rendering his mother’s story, John Ingles includes a thought that’s almost lost in the details of his narrative but which best explains her victory over the wilderness and perhaps the very core of her character:

“Her resolution bore her up.”

By Jeff Minick | The Epoch Times News Service

For further reading on this amazing pioneer, see the links below:

further reading about Mary Draper Ingles and her son John (Jonathan):

-

National Park Service – Mary Draper Ingles

A detailed history of Mary Draper Ingles’ capture, escape, and the account recorded by her son John.

Read more at the National Park Service -

Boone County Public Library – The Story of Mary Draper Ingles by John Ingles (her son)

This is a first-hand narrative written by her son John Ingles, giving a family account of her ordeal.

Read John Ingles’ account -

Blue Ridge Country – Mary Draper Ingles: The Woman Who Walked Home

A narrative exploration of Mary’s escape and the family impact, including her son.

Read the Blue Ridge Country article -

Boone County Public Library – Family Narrative and Sources

John’s narrative legacy, and historical background.

Read the Boone County Public Library narrative -

Radford News Journal – Walk to Freedom: Mary Draper Ingles’ Story

A modern retelling of Mary’s journey, her reunion with family, and her son’s role in sharing her story.

Read the Radford News Journal article

Main Photo: Kss5pj Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0