Liberty’s Torch: How Reading Fueled the American Revolution

How the printed word kindled a literate population

On Aug. 24, 1815, John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson, reflecting chiefly on affairs in Europe and Napoleon’s fall from power, but including as well this observation on the American Revolution:

“As to the history of the Revolution, my Ideas may be peculiar, perhaps Singular. What do We mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an Effect and Consequence of it. The Revolution was in the Minds of the People, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen Years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington. The Records of thirteen Legislatures, the Pamphlets, Newspapers in all the Colonies ought be consulted, during that Period, to ascertain the Steps by which the public opinion was enlightened and informed concerning the Authority of Parliament over the Colonies.”

Here, Adams does indeed offer a special take on the Revolution, known to historians but perhaps unremarked by the rest of us: The fires of liberty and self-governance were ablaze in the hearts and minds of the American people well before Paul Revere made his famous ride. The tinder, kindling, and wood for these bonfires were words, especially printed words, composed by passionate, talented writers who struck sparks not from flint and steel but from paper and pen. All that was then necessary to spread these flames was a form of mass communication and a literate public.

A Land of Readers

By 1800, only Scotland, of all the European countries, possibly surpassed the United States in literacy.

From early colonial times, settlers in the new land had stressed the importance of learning to read. The Puritans emphasized literacy for the sake of being able to read Scripture. By 1642, only 22 years after the Pilgrims had landed at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts passed a law requiring local officials to ensure that children could “read & understand the principles of religion & the capital lawes of this country.”

Though rates of literacy are difficult to determine, it is estimated that about 60 percent of white male New Englanders were literate by 1670, with that figure climbing to 85 percent a hundred years later. The South lagged behind the literacy rates of the northern colonies, in part from a lack of schools owing to more rural living. Though less stress was placed on teaching females to read, exceptions abounded. Abigail Adams and her circle of friends were readers and excellent writers, and many a mother taught her children reading at home.

The popularity of “The New-England Primer” testifies to this devotion to book learning. Estimated to be first published in 1688, Benjamin Harris’s little textbook was in use for over 150 years and sold millions of copies throughout the colonies and afterward. It remains in print today, mostly as a novelty.

In other words, an army of readers existed in pre-Revolutionary America.

Printers and the Press

In the 1750s, the average circulation of American newspapers was around 600. With the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 and the controversial attempts by the British government to tax its colonies to offset its military expenses, by 1775 the circulation leaped to an average of 3,500 subscribers per paper.

By then, too, the number of newspapers in colonial cities and towns had risen to 38. Nearly all of these were weeklies, “one large sheet folded once to create four pages roughly 10 by 15 inches in size, densely printed in three or four columns of very small type.” Editors and publishers filled these papers with national and local news, documents such as the new taxes imposed by Britain or the Declaration of Independence, and advertisements. The number of readers of these papers was far more sizable than their circulation would indicate, given that the papers often served as parlor reading for families, or were shared by neighbors or travelers in local taverns and inns.

In her article “Top 10 Printers,” Carol Sue Humphrey gives us a look at some of these early publishers of the news. Though the majority supported the cause of independence, others were either Loyalists or fence-sitters. New Yorker James Rivington, for instance, who was perhaps the most skilled of these printers, came down on the British side, saw his press destroyed and melted into bullets by a mob, began another paper, and remained a supporter of Crown and Parliament until the war’s end.

Mary Katharine Goddard was one of the few females in the trade. She took over the operation of her brother’s publication, The Maryland Journal, after he became busy helping to develop the state’s postal system. A strong advocate of the American cause, she saw to it that the paper included a copy of the Declaration of Independence less than a week after its July 4 adoption. Several months later, she printed out broadside copies containing all the signatures for the Continental Congress.

Books also played an important part in the war. George Washington, for example, read military history and urged his officers to discipline and drill their inexperienced troops by using British manuals as their guides. Good friends—Nathaniel Greene, who became a renowned general, and Henry Knox, appointed by Washington as his chief artillery officer—were both fascinated by military history, and based on their reading would frequently discuss the topic in Knox’s Boston bookstore. Long before the coming of war, these two amateurs were educating themselves in the military arts.

Franklin

Of all these printers who produced not only newspapers but pamphlets, broadsides, books, and other materials, Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was and remains the best known. Having begun his work with ink and press at the age of 12 and having worked in various print shops from New York to London, Franklin was 24 when he acquired sole ownership of The Pennsylvania Gazette.

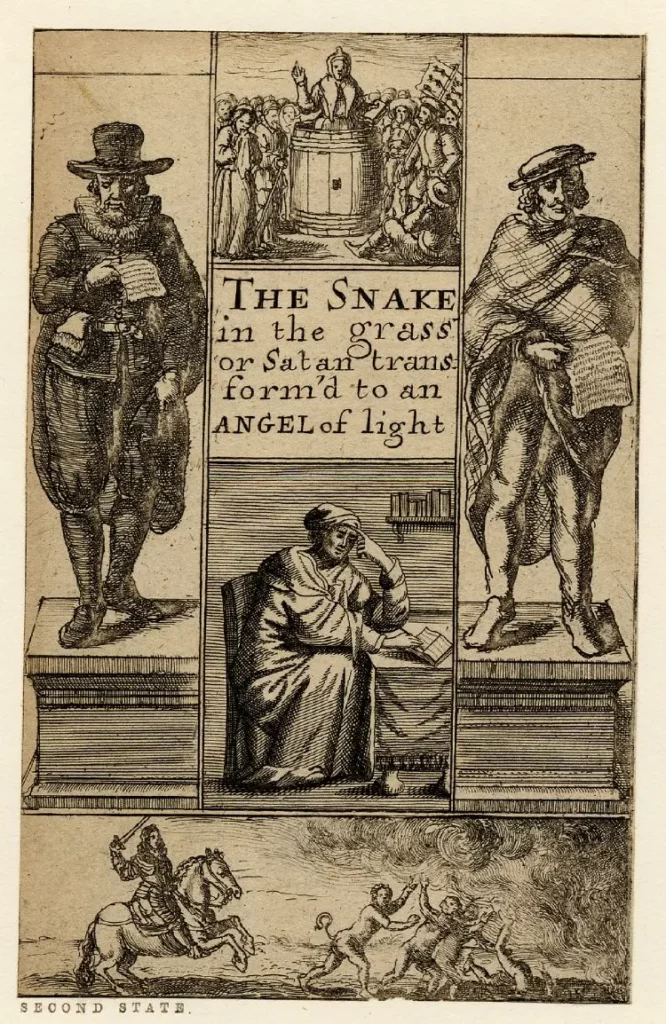

There, he published some of his own writings as well as what would become one of the world’s most famous political cartoons, the 1754 woodcut “Join, or Die.” Many mistake this image of a chopped-up snake with its pieces labeled with the initials of colonies as belonging to the Revolutionary War era, but “Join, or Die” was in fact a call for unity among the colonies when faced by attacks from the French forces and their Indian allies.

Like today’s media moguls, Franklin bought up other papers and presses throughout the colonies, acquisitions that eventually helped make him one of the richest men in America. By the age of 42, he had made enough money to retire from printing, though he retained his financial interests in this industry.

His most lucrative venture in this arena of ink was “Poor Richard’s Almanack,” which he first published in 1732 under the name of Richard Saunders. Compiled annually for the next 25 years, the almanac was a compendium of weather reports, politics, recipes, tips on finance and household management, aphorisms, stories, and jokes.

Undoubtedly, Franklin’s prestige in these endeavors helped sway others when determining their own course of action in support of the American fight for liberty.

Wordsmiths

With a growing literate audience and with the means of communication at hand, writers now stepped up and, to paraphrase John Adams, helped to enlighten and inform the public about the growing tensions with Britain and the progress of the Revolution. The most famous instances of this influence came from Thomas Jefferson and his Declaration of Independence, which was printed and distributed throughout the American states, and from Thomas Paine’s 1776 pamphlet “Common Sense,” which became a phenomenal success with over half a million copies printed over the next seven years.

Yet these men were only two of the upper echelon in a corps of writers addressing liberty and the establishment of a separate American nation. In its inventory of “American Political Writing During the Founding 1760–1805,” the Online Library of Liberty lists 515 documents, newspaper articles, books, and other publications, many of which appeared before and during the Revolution. Though we find some familiar names here, like Franklin and Jefferson, or John Adams and his cousin Sam, most are alien to us, such as Silas Downer and his 1768 “A Discourse at the Dedication of the Tree of Liberty” or Ebenezer Baldwin’s 1776 “The Duty of Rejoicing Under Calamities and Afflictions.”

Tending the Fires of Liberty

With a literate audience at hand, and with the technology available for distribution of their ideas and advice, these editors, authors, and 18th-century journalists were word-warriors for the war of American freedom. That they regarded literacy, newspapers, and free speech as crucial to a thriving republic can easily be seen in the writings of the Founders as well as in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, which prohibits the government from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

With a literate audience at hand, and with the technology available for distribution of their ideas and advice, these editors, authors, and 18th-century journalists were word-warriors for the war of American freedom. That they regarded literacy, newspapers, and free speech as crucial to a thriving republic can easily be seen in the writings of the Founders as well as in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, which prohibits the government from “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Today, just as our Founders did, we frequently struggle with these same problems. Many of our young people are graduating from schools functionally illiterate, and our press has often failed to act as a watchdog on the government. Keeping the freedom of speech alive has always required constant vigilance.

As we enter into the celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, we might take a good, hard look at these gifts bestowed on us by those men and women of America’s early days, and renew our vow to protect and preserve them.

By Jeff Minick | The Epoch Times