Ely Parker: An American Indian’s lesson of unity in a divided country

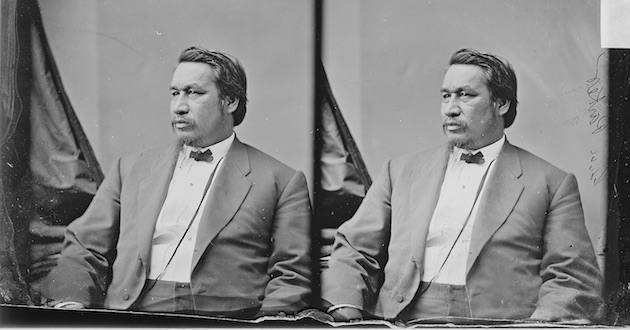

Ely Parker (born Hasanoanda, later known as Donehogawa) was born in 1828 to Elizabeth and William Parker of the Tonawanda Seneca tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy in western New York. Parker became a leader in his tribe at a very young age. Trained as a civil engineer, he earned a reputation in that field. In 1857, when he was 29 years old, he moved to Galena, Illinois, as a civil engineer working for the Treasury Department, and there his life took a fateful turn.

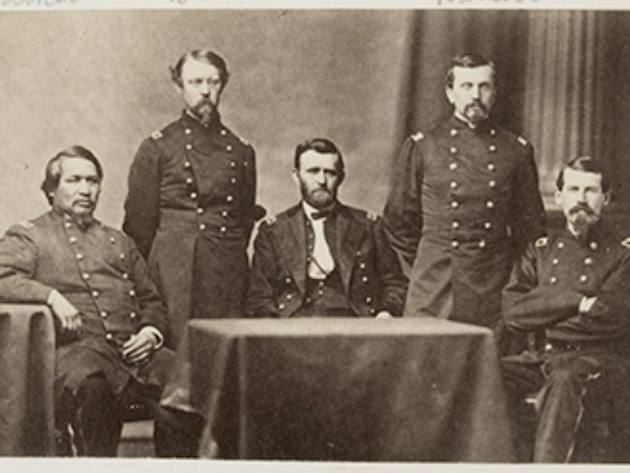

He became friends with a fellow named Ulysses S. Grant. In these years, Grant was an ex-Army officer working as a clerk in his father’s store. Parker later liked to tell the story of coming to Grant’s aid in a barroom fight in Galena, the two of them back to back, fighting their way out against practically all the other patrons. At about five feet eight inches and 200 pounds, the robust Parker referred to himself as a “Savage Jack Falstaff.”

When the Civil War came on, Parker tried several times to join the Union Army as an engineer but was turned down because he was not a citizen. When he approached Secretary of State William Seward about a commission, he was told that the war was “an affair between white men,” that he should go home, and “we will settle our own troubles among ourselves without any Indian aid.”

Eventually, with Grant’s endorsement, Parker received a commission, with the rank of captain, as Assistant Adjutant General for Volunteers. By late 1863, he had been transferred to Grant’s staff as Military Secretary. He soon became familiarly known as “the Indian at headquarters” and was promoted to lieutenant colonel and later to brigadier general. He may have saved Grant’s life or at least prevented his capture one dark night during the Wilderness Campaign in 1864, when Grant and his staff, unbeknownst to themselves, were riding into enemy lines.

But Parker is rightly most remembered for something that happened in the parlor of a private residence in the village of Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

In the days preceding, Union armies had captured the city of Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Grant and the Federal Army of the Potomac had put Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia in such a position that in the late afternoon of April 7, Grant, sitting on the verandah of his hotel headquarters in Farmville, said to a couple of his generals, “I have a great mind to summon Lee, to surrender.” He immediately wrote a letter respectfully inviting Lee to surrender and had it sent to him under a flag of truce. It took Lee a couple of days of desperate failed maneuvers to come around to the idea. But by the morning of April 9, Lee had concluded that “there is nothing left me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

They agreed to meet in the village of Appomattox Court House to discuss terms.

Grant had been riding hard for days on rough roads in rough weather. When he met Lee in the parlor of the brick house where they had arranged to meet, he had on dirty boots, “an old suit, without [his] sword, and without any distinguishing mark of rank, except the shoulder straps of a lieutenant general on a woolen blouse.” Lee was decked out from head to toe in all the military finery he had at his disposal.

After introductions, and not much small talk, Lee asked Grant on what terms he would receive the surrender of Lee’s army. Grant told him that all officers and men would be “paroled and disqualified from taking up arms again until properly exchanged, and all arms, ammunition, and supplies were to be delivered up as captured property.” Lee said those were the terms he expected, and he asked Grant to commit them to writing, which Grant did, on the spot, and showed them to Lee.

With minor revisions, Lee accepted, and Grant handed the document to his senior adjutant general, Theodore Bowers, to “put into ink.” This was a document that would effectively put an end to four years of devastating civil war. Bowers’ hands were so unsteady from nerves that he had to start over three or four times, going through several sheets of paper, in a failed effort to prepare a fair copy for the signatures of the generals.

So Grant asked Ely Parker to do it, which he did, without trouble. This gave occasion for Lee and Parker to be introduced. When Lee recognized that Parker was an American Indian, he said, “I am glad to see one real American here.”

Parker shook his hand and replied, “We are all Americans.”

***

The American story, still young, is already the greatest story ever written by human hands and minds. It is a story of freedom the likes of which the world has never seen. It is endlessly interesting and instructive and will continue unfolding in word and deed as long as there are Americans. The stories that I think are most important are those about what it is that makes America beautiful, what it is that makes America good and therefore worthy of love. Only in this light can we see clearly what it is that might make America better and more beautiful.

Christopher Flannery is a senior fellow of the Claremont Institute, contributing editor of the Claremont Review of Books, and host of The American Story podcast at theamericanstorypodcast.org. He is a professor emeritus of the Honors College at Azusa Pacific University, where he taught for over 30 years. He received his M.A. in International History from the London School of Economics and Political Science and his Ph.D. in Government from the Claremont Graduate School.