The Netflix show “Tiger King” caught the attention of millions of viewers back in March. The “murder, mayhem and madness” suggested in its subtitle collided in a human train wreck of a drama — but it got Steve Klein’s attention for a different reason.

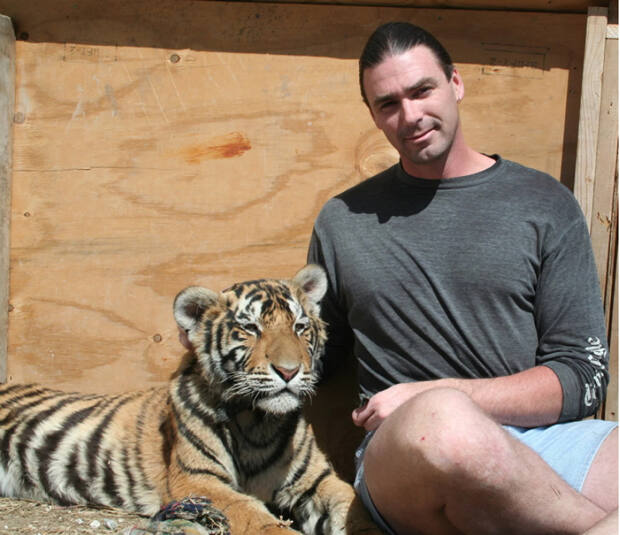

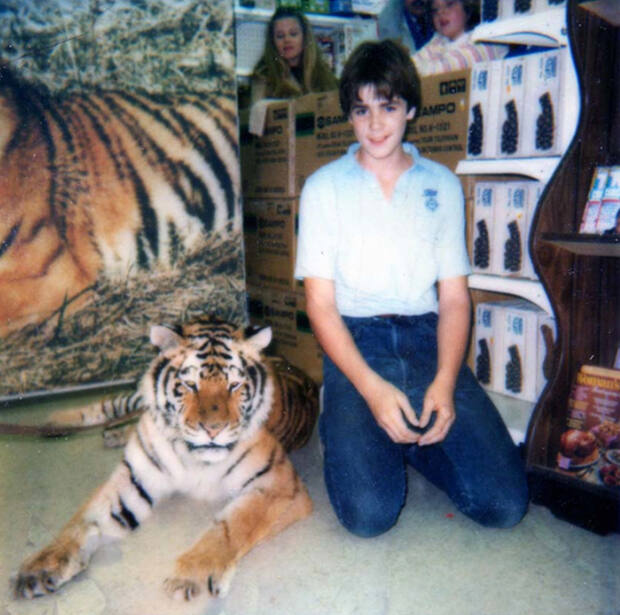

Klein is the board president and resident curator at Cedar Cove Feline Conservation and Education Center in Louisburg, Kansas. A variety of 28 predators are in his and about 20 volunteers’ care.

He can rattle off their species and names, but says his ability to remember them all isn’t about having a great memory.

“When they become family, it becomes easier — but it’s a big family,” Klein says.

READ: Chiefs’ owner Clark Hunt looks to past to guide decisions during tumultuous times

Klein has volunteered — now full-time for an annual stipend of $12,000 — at Cedar Cove for 20 years. The mission of the center is to care for animals and to educate the public about the importance of keystone species within the global ecosystem.

He says humans are demanding too much of the ecosystem for just one species, taking more than our share. And animals are paying the price.

“Now, why are we so concerned about the animals? Because these animals are literally the key to the health of these environments and ecosystems that they occupy,” Klein says. “They’re not just apex predators, more importantly they’re called keystone species.”

He illustrates the idea with what happened at Yellowstone Park when wolves were removed. The population of grazing animals grew until it destroyed the balance of the park by eating up everything that birds, pollinators, and insects needed for food or habitat. Balance was eventually regained after two seven-wolf packs were reintroduced to the park in 1995.

Klein talks to the cats, wild dogs, and fox as if they were his own — and in a way they are, because none of them can be released in the wild. Each one has a fairly tragic backstory, some worse than others, but all ending in needing a new home.

The oldest resident is Voodoo, a 19-year-old African Spotted Leopard. Klein greets him like he might any buddy: “Voodoo man!” and then makes a deep woofing sound, as if speaking a leopard language.

When the big cat approaches the tall security fence, Klein says, “He came from a domestic situation. A couple purchased him to be a house pet.” Before Voodoo was even six months old, the people thought better of their decision.

“He’s going to come over for a belly rub,” Klein says. The big cat flops on his back and as Klein pets him through the fence, Voodoo growls and makes a sound like a thunderous purr.

In reflecting on “Tiger King,” Klein says, “These animals are so mesmerizing, it’s hard not to see them being as sensational as you want to see them being.”

But, he says, the show wasn’t actually about the animals at all. “The people involved weren’t doing anything to help the animals; it was all to exploit the animals,” Klein says. “It wasn’t to make their lives better in captivity or to try to further the survival of the species in the wild.”

Delcianna Winders is the director of the animal law litigation clinic at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. She knew about Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin, the main characters in “Tiger King,” long before most people did.

She draws a sharp distinction between the show’s warring facilities — Baskin’s is accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries and Joe Exotic’s is not. She says GFAS is the gold standard for the business, but only 15 facilities in the entire nation are certified.

At least 100 other places call themselves sanctuaries, refuges, or havens, including Cedar Cove. Without that accreditation, Winders says the businesses fall into a grey area; to stay open, they need to be inspected by the department of agriculture, local game warden, or some other governing body.

However, Winders says, “when you get into more nuanced things like adequate space, adequate veterinary care, that’s really hard for a lay person to know and to assess, and that’s where the third party accreditation like GFAS comes in.”

The popularity of “Tiger King” has gotten the public talking more about the well-being of big cats, which Winders is glad about. But, she knows the average viewer still isn’t quite sure what type of place is okay to support and what isn’t — both Baskin’s and Joe Exotic’s businesses were thriving.

“There are some clear red flags. Breeding animals is absolutely a red flag,” Winders says. “Another red flag is allowing public interaction with animals because that seeds, basically, a puppy mill operation where they’re constantly breeding animals to have some that are small enough for public encounters.”

She’s read reports about Cedar Cove and notes that it doesn’t engage in those bad practices.

Klein and Winders agree that these animals don’t belong in captivity, but until people stop breeding wild animals, they’ll continue to need safe places to live out their lives. According to the World Wildlife Federation, only 3,900 tigers exist in the wild.

Winders says that more than that live in the backyards and basements of America— estimates say as many as 20,000 tigers may live this way. “Because of lack of regulation, we actually have no idea,” she says.

Klein says, “We are a sanctuary to give these animals the best possible lives we can with the means at hand.”

And what he asks of the animals in return is to hold an audience captive long enough that a Cedar Cove guide has time to explain how and why the animals are in cages in the first place, and why that’s a tragedy.