Christians in Kansas City love the Chiefs, but hate the city’s violence

Even before last week’s shooting at the Kansas City Chiefs Super Bowl rally, Branden Mims was focused on reducing violence in this city that amassed a record 182 homicides in 2023.

Mims, the 35-year-old senior minister for the Greater Metropolitan Church of Christ, leads a faith-based nonprofit called Greater Impact that served more than 400 shooting victims last year.

“Most folks are up in arms about the shooting at the Super Bowl parade,” the preacher said before leading a special prayer Sunday. “But I was up in arms before then.”

“Amen! Amen!” the congregation responded.

“Everybody keeps saying that this is not Kansas City, but it is,” Mims told members. “The sooner we accept it, the faster we can change it.”

Missouri’s largest city — with a population just over 500,000 — has one of the highest murder rates in the nation, the minister noted.

“Lord, we ask that you would turn this city around,” Mims prayed. “We ask that you would bless us to … continue to be the emergency responders to help bring souls to Jesus. And Lord, we pray that tonight there will not be another homicide.”

“Yes, Lord! Yes, Lord!” agreed Mary Johnson, 61, seated in a pew toward the back.

Johnson wore a black shirt with white letters that declared, “I will walk by Faith, even when I cannot see.”

“God moves,” the Chiefs fan said after the assembly. “He’s going to move in this city. He’s going to stop all this stuff that’s going on.”

Not deterred by shootouts

Greater Impact operates out of the church, which just a few years ago erected its purple-carpeted building — with a coffee shop open to recovering drug addicts — in the heart of the city.

“There have been shootouts on the backside of the church, and unfortunately, sometimes the building gets hit,” said Mims, who started the church in a storefront in 2013. “We just repair it and keep going. We came into this area on purpose.”

Two other preachers work as community outreach specialists for Greater Impact: Cedric Finley of the Inner City Church of Christ in Kansas City, Missouri, and Chalmers Richardson III of the Madison Avenue Church of Christ in Wichita, Kansas.

“We all preach for three different congregations,” said Mims, Greater Impact’s executive director. “We absolutely love the work we do. On Monday, we assemble in Kansas City and go to work reducing violence.”

The urgency of Greater Impact’s mission was reinforced by the Valentine’s Day shooting that claimed the life of Lisa Lopez-Galvan, 43, a popular DJ and mother of two, and left 22 other people — half of them children — bloodied by bullets.

“We know that we live in a city that needs prayer, as we saw demonstrated Wednesday,” said church member Marcus Hicks, 52, who sported a knit cap with a Chiefs logo on a chilly Lord’s Day.

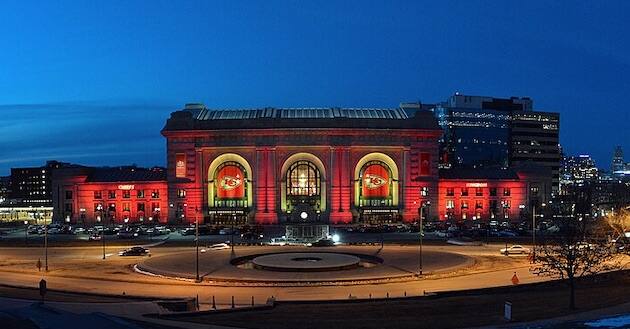

The gunfire near the city’s Union Station stemmed from what appeared to be a dispute among several people, police said.

The violence came at the end of a parade and rally that brought an estimated 1 million people to Kansas City to celebrate the Chiefs’ third Super Bowl win in five years.

Authorities have charged two adults and two juveniles with crimes ranging from murder to gun-related offenses. Additional arrests are possible, Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker said.

Kansas City has long struggled with gun violence: In 2020, it was among nine cities targeted by the U.S. Justice Department in an effort to crack down on violent crime in the Black community, The Associated Press reported.

“I don’t understand the shooting, Lord. I just don’t understand the shooting,” Harold Taylor, 82, prayed Sunday at the Greater Metropolitan church’s second location in suburb of Belton.

Taylor, a U.S. Army veteran, drove a school bus full of Chiefs staff members to the parade. After the worship service, he tapped his heart as he recalled hearing the gunfire.

“I was on the way back to the bus, and it was just, ‘Bam! Bam! Bam! Bam!’” he said.

When he was a boy, Taylor said, a fight between young people might result in a busted lip or a black eye.

“But then the next week you were just patting each other on the back and shaking hands. Where’d this shooting come from?” he asked, wondering if TV and movies might be responsible.

Melesa Johnson, Kansas City’s director of public safety, agreed that a “praise culture of violence” in the entertainment industry contributes to the problem.

“And then, when you marry that with poor conflict resolution skills, it really puts our young people … in a state where they’re very vulnerable to violence,” Johnson told The Christian Chronicle. “And that, unfortunately, is what we saw take place on Wednesday.”

A turning point

Minister Mims grew up poor in Atlanta.

He traces his passion for urban ministry to his late cousin David Mumford’s shooting death about 15 years ago.

Staring at the casket of his cousin — just a year older than Mims — made the future preacher realize, “When it’s my turn, what will matter will be what I did for God.”

That’s when he decided to attend Southwestern Christian College in Terrell, Texas, where he earned a religious studies degree in 2011. He preached for the Swope Parkway Church of Christ in Kansas City before planting the new congregation.

Greater Impact — established as a 501(c)(3) organization by the Greater Metropolitan church in 2022 — focuses on victim services.

The nonprofit’s offerings, funded by grants from government agencies, range from trauma counseling to workforce development.

“So we start putting those pieces back to their life,” Mims said. “But the caveat is, we do it with preachers because we have a kingdom element to it. And we’re looking, ultimately, to point them to Jesus.

“We don’t press them on it,” he stressed. “It’s not a thing where we formally sit down with them and have a Bible study. But we navigate it (in such a way) that we just show them God.”

Assessing victims’ needs

After receiving a referral, minister Finley said he typically will call a shooting survivor.

He’ll introduce himself and ask about the person’s needs.

“I’ll say, ‘I understand you’ve been shot in the leg, and you’ve been off work for three weeks. Is there anything we can do to help?’” said the 61-year-old preacher, who has extensive experience in prison ministry. “They’ll say, ‘Well, I need groceries.’”

That’s no problem, he’ll reply.

“The gratitude is really beautiful, but that’s a typical call,” Finley said.

Minister Richardson, 37, who attended Southwestern with Mims, said he tries to understand the root causes of a person’s brush with violence.

He asks questions such as, “Do they need food in their home? Are their utilities getting ready to be shut off? Water? Are they about to get evicted? Do they need trauma counseling?”

“My job,” he explained, “is really to assist the family and to really pull out things to see what else they need.”

Fatigue and faith

Sharee Mims, Branden’s wife, is a licensed clinical social worker. She serves as Greater Impact’s clinical director.

“Everyone that’s referred to our program has been impacted by violence in some way,” Sharee said. “Either they’re the family member of someone that was murdered or they’re a shooting victim, meaning they survived a shooting. And a lot of times they need trauma therapy.”

Even though not all victims are open to conversations about God, Sharee said her own faith helps her persevere.

“You do gain some fatigue from this work, from hearing horror stories,” the mother of two young children said.

She recalled a 21-year-old client who had been shot 18 times and experienced a traumatic brain injury.

The woman had a young daughter the same age as Sharee’s daughter, who is almost 4.

“So listening to that and seeing her, that was hard,” Sharee said. “I think my faith helps me maintain that compassion, that grace. … I know I have someone — God — to help me process through all that.”

Johnson, the public safety director, characterizes Greater Impact’s community impact as “amazing.”

Many people touched by violence are leery of police officers, said Johnson, who was appointed by Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas.

“Given their position as leaders in the community, as faith leaders, Pastor Mims and Sharee bring a different credibility to this space,” Johnson said. “Our police department does have social workers on staff, but they still wear badges.”

Greater Impact’s staff is “able to have conversations with the community that law enforcement simply cannot have,” the city official added. “And I think it really opens up people’s minds and ability to receive services when they’re being offered.”

The church is ‘a safe place’

The nonprofit receives about $300,000 a year through Jackson County’s Community Backed Anti-Crime Tax, known as COMBAT.

Vincent M. Ortega, COMBAT’s executive director, is a former Kansas City deputy police chief. He praises the positive difference made by Branden Mims and Greater Impact in the community.

Even before launching Greater Impact, Mims began working in 2016 with the AdHoc Group Against Crime, a violence prevention organization in Kansas City. He now serves as AdHoc’s chief operating officer.

When looking for a hub to receive non-fatal shooting referrals in Kansas City’s Midtown, Mims’ church made sense, Ortega said.

“That was an area where we had a lot of violent crime just in and around his church,” Ortega said.

The collaboration between a government agency and a faith-based organization has not created any issues, he said.

“It was a blessing to get churches involved,” Ortega said, “because they’re there in the community. It’s a safe place. It’s a neutral place, too.”

Bullet hole in the nursery

Brian Wroten, a Greater Metropolitan church member and Chiefs season ticket holder, owns a construction company.

He serves as an independent contractor for Jackson County’s Caring for Crime Survivors.

“What I do for the program is, I repair homes of victims that have been shot up and just basically destroyed through crime,” the 56-year-old Christian said.

“It’s tough sometimes to go into the homes and see some of the results of violence that I see,” added Wroten, who leads the church’s food pantry ministry. “I often find comfort in talking to the victims and sharing God with them. And I let them know that there’s hope in Christ.”

He’s called upon, too, to make repairs when the church building gets caught in the crossfire.

“In fact, there was a bullet hole in the nursery that I patched not long ago,” he said. “It happens.”

Toni Austin-Booze, 44, a mother of three sons, volunteers as a Greater Metropolitan church greeter and helps with the food pantry.

In addition, she directs Greater Impact’s metal detector screening program, which works to keep firearms out of a major entertainment district near the church.

“I think we’ve just got to continue to spread the love and the Gospel,” Austin-Booze said, “to bring souls to Jesus, to show people there are alternatives, to get people to see value in their own lives so that they can value the lives of others.”

The church celebrated the baptisms of two new Christians this weekend, including a man taught the Gospel after he showed up looking for an addiction recovery meeting Saturday.

In a sermon, Branden Mims likened the role of Greater Impact’s ministers to that of spiritual paramedics.

“When we hit these streets, y’all,” he told fellow Christians, “all we’re doing is walking up to people and doing CPR on their hearts.”

–By Bobby Ross Jr.

This piece is republished from The Christian Chronicle.

Bobby Ross Jr. writes the Weekend Plug-in column for ReligionUnplugged.com and serves as editor-in-chief of The Christian Chronicle. A former religion writer for The Associated Press and The Oklahoman, Ross has reported from all 50 states and 18 nations. He has covered religion since 1999.