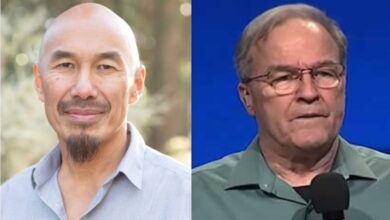

Edward Peecher: From the Black Panthers to seeking peace on Chicago’s violent streets

For Edward Peecher, promoting peace in Chicago’s violent streets is a long way from his days as a member of the Black Panthers. Now 70 years old, the pastor remembers what took led him to the Panthers and, ultimately, a relationship with Christ.

Televised images from the civil rights struggles in the South in the mid-1960s seared into Edward Peecher’s brain: pictures of African Americans being evicted for staging peaceful lunchroom protests; being bitten by police dogs; being beaten by police officers who should have been protecting them. The ongoing footage stirred ire in the passionate teenager.

“I thought there was no way for those kids to be in this fight with me on the sidelines,” says Peecher, the middle of seven children born to a steelworker father. The angst continued to foment.

In 1968, at the age of 18, Peecher joined the Black Panthers revolutionary group, but soon became disillusioned.

CAREER TRANSFORMATION

In 1969, the smart and ambitious Peecher left the Black Panthers and found a job as a cable splicer with AT&T. Soon after, he accepted Jesus as Savior. He says the decision stemmed from the Holy Spirit pressing on his heart about life’s meaning and final judgment. Childhood memories also played a role.

Peecher grew up in a Catholic home and went to Catholic schools. However, for the most part, he says the instructors didn’t exude joy at his presence but did teach about sin.

“One vitriolic and vocal nun made sure to let me know I was a sinner,” Peecher recalls. “That later became the basis for my salvation. I thank the nuns who hated my guts for bringing me to the place where I needed to give my heart to Jesus.” His life-changing decision happened at 23.

Video: Peecher interviewed in 2016:

Within two months of being saved, Peecher enrolled in Moody Bible Institute. He discovered he had a knack for evangelism, telling friends, fellow employees, and relatives about Jesus. He led his parents, wife, sisters, brother, and children to the Lord. Peecher also started multiple Bible studies. A weekly lunch get-together to learn Scripture with a co-worker mushroomed into a Bible study with 40 people.

Job promotions came repeatedly at AT&T. By the time he left after 17 years, he worked as a senior account executive, selling large business telephone systems to Fortune 500 companies. Those in the Bible studies became the nucleus of the Assemblies of God congregation he founded, now known as Chicago Embassy Church Network. In 1986, he left his good-paying job at AT&T to pastor full time. The AG ordained Peecher the following year.

A BLACK VOICE

About the same time, the leader of the Assemblies of God said the future of the denomination looked urban, as well as Black and Hispanic. Peecher was tapped by a missions leader to be on the agency’s board. In 1992, Peecher became the first African American presbyter in the U.S. Assemblies of God.

At the same time, Peecher also ascended to the presidency of the Inner-City Workers Conference, the precursor to the AG’s National Black Fellowship (NBF). The AG looked a lot whiter in those days than it does now (currently more than 11 percent of adherents are African American). Thirty years ago, the AG had under 100 Black-majority churches; now there are more than 450. Peecher knew how to navigate in a white-dominated cultural environment.

“I fit into the corporate white man’s world at AT&T,” Peecher says.

After some intense discussions about tokenism, the Inner City Worker’s Conference dissolved, with the assurance that the leader of the NBF would have a seat on the AG Executive Presbytery.

A VOICE FOR PEACE

Crime and violence continue to plague Chicago, as they have for many years. Peecher has long been a voice for peace. The church Peecher pastored stood on the corner of 59th and Princeton, the dividing line between two gangs: the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples.

In 2006, after a spate of increased shootings, Christian volunteers occupied the corner of 59th and Normal for 12 hours beginning the Friday night of Memorial Day weekend, the likeliest time for killings to occur. The church set up floodlights and Christians sang hymns on the corner. On Memorial Day last year, 80 churches mobilized on metro corners in a similar peace campaign effort to bring salt and light through hip hop and modern gospel music; no shootings occurred throughout the Windy City during that span.

TOGETHER CHICAGO

Together Chicago hopes to increase such efforts once the coronavirus eases up. The nonprofit, launched in 2017, is comprised of Chicago business, community, government, and faith leaders addressing the root causes of violence. Mobilizing Christians is a key component in seeking justice.

“Our goal is to have churches adopt hot spots near their block, building a wall as Ezra and Nehemiah did,” Peecher says, referring to the Old Testament prophets who oversaw the reconstruction of a crumbling Jerusalem after exiles returned. “Going forward, Chicago will be a model of cooperation between institutions in the city and the Church. We want to coordinate efforts to bring justice, peace, and economic development.”

In 2016, Peecher received a diagnosis of liver cancer, a disease with a 96 percent mortality rate within five years if the disease spreads. But Peecher is fully recovered after treatment. The year of his diagnosis he turned leadership of Embassy Church, a predominantly African American congregation, over to Chris M. Butler.

Butler, 36, has known Peecher since the age of 10. He grew up in the church and Peecher served as a mentor. Butler says Peecher pioneered many of the Together Chicago education, housing, and educational initiatives at Embassy Church.

Butler says he is most grateful that Peecher taught him to stay close to and to love Jesus. His mentor has discipled many people, Butler says, with an ability to adroitly unpack complicated situations.

“Bishop is incredibly faithful and wise — and completely fearless,” Butler says of Peecher. “I admire his integrity. He is the same guy at home as he is in the pulpit.”

These days, Peecher is trying to achieve some of the same goals as more than a half-century ago, but through a different lens as well as by different means. One of Together Chicago’s education initiatives focuses on helping young African Americans learn to read.

“By third grade, children need to transition from learning to read to reading to learn,” Peecher says. “If they don’t, they will likely drop out of school eventually and end up in jail.”

Peecher started as a volunteer with Together Chicago. He now is chief operations officer. Together Chicago also advocates enlisting volunteers to assist in public school classrooms, which especially helps the environment if the teacher is trying to deal with a disruptive or distracted pupil.

“If there is more than one caring adult in a learning environment, children will learn more,” says Peecher, who has been married for 49 years to his high school sweetheart, Katie. “Grandma knows how to handle the one student so the teacher can focus on the rest of the class.”

A total of 22 public schools have connected to churches in the cooperative, but no one is protesting about church-state boundaries being breached, according to Peecher.

“We unabashedly come in and say we’re going to bring church volunteers to help the teachers,” says Peecher, who remains an ordained AG minister. “Nobody questions it, because the results show improvement in test scores.”