The little-known Civil War history of Cass County

On July 11th the Burnt District presented a plaque marking the bloodiest battle of the Civil War in Cass County, Missouri. It honors the Battle of the Ravines, and for history buffs like me, I am suddenly interested in a battle that was so important that it resulted directly in the declaration of General Order Number 11. That was the only time that the US used its military to fight and injure its own citizens. It was a time when atrocities were committed on both sides, but the victors writing the history books only hint at devastation caused by the government.

History is both local and selective. The average high school student can name the battles from Gettysburg to Vicksburg in the history of the Civil War, but only local students understand that the war went beyond the Mississippi River.

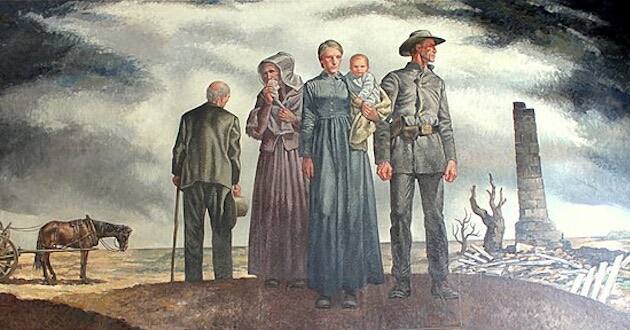

Fewer still know that, in the study of the war, only Tennessee had more battles than Missouri. Fewer still can note the trauma of General Order Number 11, its declaration, results, and context surrounding it, and even the locals are clueless about the factors that caused it, and there is a misconception that the Burnt District deals with Harrisonville more than the rest of Cass County, but there is a painting in the Truman library that testifies to the horror.

The rift between Kansas and Missouri runs deep, and the hardship of John Brown and the Missouri Compromise remained throughout the war. They did not end with an Act of Congress or the settlement of the slavery issues in Kansas. As we have pointed out before, there are quirks of history that help define it, like the creation of the Colorado Territory upon Kansas statehood and naming the Colorado Territorial Capitol after the first governor of Kansas. History is context.

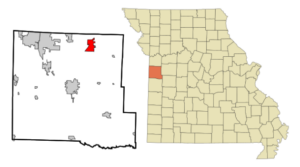

Pleasant Hill, established in 1844, was a crossroads of trails running north and south and east and west. That fact is one of the reasons why Pleasant Hill had several different railroads after the war. The town saw some 15 different skirmishes, during the war. Most of Cass County’s settlers were from southern states, so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that in the election of 1960, when there were no secret ballots, Abraham Lincoln received only 23 votes in Cass County.

In 1861, with the beginning of hostilities, Missouri had two governments, and the state was represented by stars on both the US and Confederate flags. There was no Union Army or Confederate Army, per se, but a coalition of state forces raised by each state to fight and, between June and November, Kansas Rangers raided western Missouri.

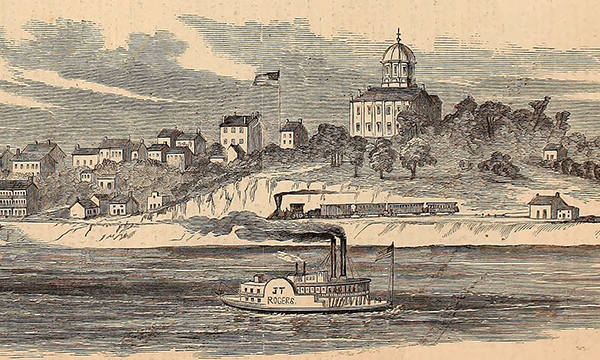

In October a sweep by Kansas General Lane into the Pleasant Hill area yielded threats to the community and a captured Confederate flag. Pleasant Hill residents responded by destroying two government wagon trains supplying Jefferson City, and on November 18, 1861, Colonel Jennison of the 1st Kansas Cavalry burned much of Pleasant Hill. So nasty were the Union attacks that General Halleck, writing to General McClellan, stated that due to the damage caused by Union Kansas Forces, he might need an additional 20,000 troops to bring peace to Missouri. In January of 1862, a company of the Kansas 7th Cavalry was sent to Johnson County, Missouri to confront Confederate forces, and they ended up burning the town of Columbus to the ground, and passing through Pleasant Hill, they appropriated $10,000 worth of livestock and grabbed fifty-five slaves.

On the Confederate side, much of the fighting was done by William Quantrill. He had settled in Lawrence, Kansas in 1859, where he taught school. In 1961, being charged with murder and theft, he fled Lawrence running to Missouri. In the early part of 1961, he joined the Confederacy, but later broke with the regular forces to establish his own group of raiders. His band of guerillas using hit and run tactics, served both themselves and the Confederacy before the Confederacy had any real organization in Western Missouri.

Leading up to the Battle of the Ravines, the Confederate government in Missouri was flooding Cass and Bates Counties in Missouri, recruiting soldiers for the Confederacy. Most Confederate forces had retreated to Arkansas and Texas in 1861. Quantrill’s Guerillas mauled about 90 soldiers of the 1st Iowa Cavalry at Sugar Creek on the Cass-Johnson County border. Their commander, Major James C. Gower, was so disturbed by the defeat that he summoned all the Union troops in the area to track and destroy Quantrill. Along with Gower’s 75 remaining men, were 65 from the 1st Iowa under Captain Ankeny from Clinton, 65 men of the 7th Missouri under Captain William Martin from Warrensburg, and 63 men from the 1st Missouri Cavalry under Captain Matin Kehoe and Lieutenant White from Harrisonville. creating a force of about 250 men. They tracked Quantrill’s forces across Cass County for about 50 miles to the Sorency farm located about 4 miles west of Pleasant Hill at what is today the junction of 175th Street and Highway BB.

Gower wanted to surround the approximately 120 raiders and with combined forces take or kill Quantrill who rested nearby on July 10th. Whether Captain Kehoe misinterpreted his orders to wait or not, he led a charge down the Sorency farm lane and was injured it the first volley. Quantrill’s forces, caught unmounted, retreated to the ravines behind the farm as the rest of Gower’s forces found and surrounded Quantrill’s men with fighting done at a range of about 50 feet. It would mark the only battle in which Quantrill’s forces fought dismounted. Quantrill, outnumbered, ordered his men to disperse, and using the ravines slipped right through the union lines. Quantrill was shot in the thigh, and his forces lost their horses and muster roles. There were no prisoners. The union forces had twenty-six dead, and thirty-five wounded. The best accounting of Quantrill’s men was eighteen dead and some twenty-five to thirty wounded.

One month later on August 11th, Confederate forces that included Quantrill, took Independence, Missouri, and on August 16 some 900 Union soldiers dispatched to break up Confederate recruitment in Cass and Bates County came face to face with about 1,200 Confederate soldiers in Lone Jack, Missouri. The Pleasant Hill Union Commander, Captain Long was mortally wounded while supporting the Union center in the battle, and he returned to Pleasant Hill commanding from the Henley Household, a farm on what is today North 7 Highway.

On October 7, 1862, Cole Younger, leading a portion of Quantrill’s raiders took Pleasant Hill, scattering the Union forces camped at the old fairground. No citizens were hurt as they were herded into the Methodist Church.

From October of 1862 through the summer of 1863, the area was marked with border incursions, Kansas forces burning Missouri towns, and Quantrill attacking Kansas towns. He even attacked Olathe, the Johnson County seat. During that time union forces began collecting the families of all the fighters found on Quantrill’s muster sheets. The women were consigned to a Union prison in Kansas City. Their homes and farms were burned.

On August 13, 1863, the overcrowded women’s prison where all of the Confederate women were incarcerated collapsed, killing four women and injuring others. Some were disfigured and disabled permanently.

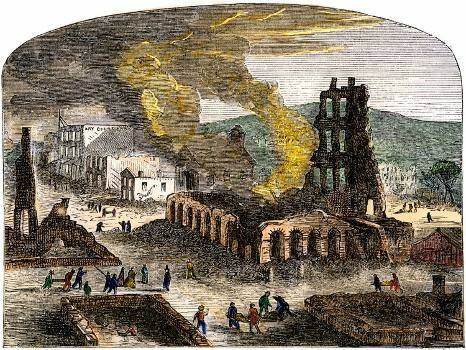

News spread quickly, and Quantrill’s raiders now numbering 400 men set out from the area around Pleasant Hill Lake headed west. The approach to Lawrence took three days, and by the time Quantrill entered Lawrence, his ranks had swollen to about 450 men. On August 21, 1863, Quantrill and his men burned most of Lawrence, Kansas. Killing 183 civilians, mainly men and boys.

Four days later, on August 25, 1863, Union General Thomas Ewing issued General Order Number 11, ordering all residents of southern Jackson, all of Cass and Bates, and the northern part of Vernon Counties to relocate near Federal encampments in Pleasant Hill, Harrisonville, and Kansas City. All buildings were burned, livestock either taken or destroyed, and those pledging to the union were allowed to stay in the affected areas, despite the destruction of their homesteads This marked the only time when Federal Troops have ever been used against a county’s citizens without compensation.

In January of 1864, General Brown taking over for General Ewing admitted that General Order Number 11 was a mistake, creating Confederacy supporters out of Union supporters and those who wanted to remain neutral, but the damage had already been done. His order allowing those that supported the Union to return to their homesteads, sans livestock, crops, and farm equipment were never repaid. During the battle of Westport, some 33,000 troops were engaged by both sides, a testament to the number of Confederate soldiers, many created by General Order Number 11.

There is not a single building in Pleasant Hill that predates the Civil War, even though the city was established some 16 years before the War began.

The Battle of the Ravines was not a battle with extreme loss of life, but it was the battle that paved the way for the Union tragedy of women in the Kansas City prison collapse, the raid on Lawrence, and treatment under General Order Number 11.

It is true that Quantrill and his guerillas were extremely violent, but the Union Army was no less violent, particularly the Kansas soldiers that burned towns in Missouri. They were called Jayhawkers and Red Legs, and their histories of violence did not end with the Civil War.

–Bob White is a published author and lives in Pleasant Hill. He regularly writes about history for Metro Voice.