‘The Father’ is an intimate look at dementia and a daughter’s dedication

The Father is a beautifully honest portrait of dementia and the toll it takes not just on the one suffering from it, but on the aging man’s primary caregiver: his daughter.

The mind, like the body, is a creation of dizzying intricacy. Just as we don’t think about how the heart beats or the lungs breathe, neither do we question what our brain tells us is true.

But sometimes, something in the brain breaks. Clogs. Slows. Skips.

If the body goes wrong—the heart, the lungs, the legs, the teeth—we know it. We feel it. We do something about it, because our mind tells us we must. But when the mind goes wrong, it doesn’t look, to us, as if it’s broken. It looks as if the world has.

Anthony (Anthony Hopkins: Amistad, Nixon, The Two Popes, Remains of the Day) knows his world. He knows who he is, what he loves and how he spent his life. His walls are filled with books and records and pictures of the past, evidence of a life well-lived. He has two grown daughters—one he barely sees and loves, the other is Anne (Olivia Colman: The Crown, Broadchurch) whom he sees all the time and … well, she’s just all right.

Perhaps he’d appreciate Anne more if she wasn’t always around. But she is. It’s as if she’s moved in to his flat, and at an age when she should really be out on her own. She has a husband named Paul, too—or, at least she does part of the time. And then there are the strangers that Anne insists on bringing in: nurses or helpmates or whatever they’re called. As if Anthony needed help. As if he was old and feeble and not perfectly capable of living his life as he always has.

No, these “helpmates” are of little help to Anthony. They’re terrible, in fact—babying him incessantly and, often, stealing things when they believe he’s not looking. He’s been forced to hide his most prized possessions in a cabinet or under the tub.

But the worst of it? The strangers that come in—those who say they’re Anthony’s caregivers. Those who say they’re Paul. Those, even, who come in and pretend to be Anne herself. What sort of trick are they trying to pull? Anthony knows what his own daughter looks like. Why, he can point to her picture right on that—

But where’s the picture? And who painted the wall?

Many of us know, too well, how much Alzheimer’s and dementia can take from loved ones. So to do we recognize the quiet heroism that comes with caring for someone suffering from the condition.

REVIEW: Where’d you go Bernadette explores mental illness

And, indeed, Anne is quietly heroic here. We see her suffer a great deal from her father’s slights and suspicions. When Anthony tells visitors that Anne is dull and tedious, she forces a smile and tries not to cry. When Anthony has lost one of his prized possessions, Anne does her best to calm her dad and find it for him. She’s always on call and ready to rush to her father’s side if something goes wrong, sacrificing her own freedom and happiness to do so. Sometimes she even sings him to sleep, as a mother would a baby.

But while Anthony can sometimes act monstrous, it’s not his fault. And just as we can see his cruelty, so too we see flashes of kindness and gratitude.

“Anne,” he says. “Thanks—for everything.”

Like countless caregivers know and understand, we see that Anthony can be un relentlessly cruel and Anne’s struggle to not to acknowledge it when others are blind to it.

“I must say, he’s charming,” caregiver Laura (Jane Eyre, Miss Austin Regrets) tells Anne when she first meets Anthony.

“Yeah, not always,” Anne says with a forced smile.

We see Anthony behave quite cruelly on occasion, especially toward Anne. “She’s not very bright,” he’ll tell someone as Anne looks on. “Not very intelligent. She gets that from her mother.” He accuses Anne of plotting against him and waiting for him to die so she can have his apartment. “I’m going to outlive you,” he bellows, telling caregiver Laura just how “heartless and manipulative” Anne is.

Anne is devastated and embarrassed by Anthony’s outburst, but Laura takes it in stride. “That sort of reaction is quite normal,” she says. But that doesn’t mean Anthony’s abuse is easy for even professionals to stomach. We learn that he’s chased off several—accusing them of stealing from him and being generally mean.

But what is there to learn in this family drama? For many, it will resonate with their own experiences. For others, it will provide insight into the care a friend, sibling or neighbor offers to an aging parent.

We can lose our possessions, but no one can take away our memories.

So we tell ourselves as we spend time with loved ones and our money on family vacations, squirreling away precious, eternal moments at every turn.

But the cliché, we know, isn’t always true. Our memories can be taken from us. Our intelligence can, too. Our wit. Our very personality. Everything that makes us us can be torn slowly away, like pages in an old book, until all that’s left is the cover. A empty book jacket of who we were.

To me, this feels like one of life’s greatest and cruelest challenges, one that can even shake faith. God, we might pray, take from me my wealth, my health, my home … but leave me myself. Let, with my last breath, look into the eyes of those whom I love, and let them know that I love them, too. But for some, God does not grant this prayer. God is good, but His ways can be mysterious and hard.

READ: Don’t dismiss value of Disney+

The Father, of course, is a very sad movie, one that mercilessly marches through the realities of fading by inches. For those who are intimately acquainted with the subtle horrors of Alzheimer’s and dementia, the film might be especially hard.

But it might be welcome, too, for the film comes with its own bleak beauty It carries with it, perhaps, the tang of grief—all the sorrow and sadness and anguish and pain that great loss brings, but moments of strange sunlight in the darkness: Because in the midst of grief, love remains. Love goes on.

I am not myself, Anthony tells us in gesture and deed. But as the movie wears on, an important but comes about. I am not myself, it says, but I am worthy of love still. I care still—and need care. I am not myself, but I am still a beautiful thing—a beloved creation.

The Father features two incredible performances by previous Oscar winners Anthony Hopkins and Olivia Colman. And while it has some bursts of foul language and moments of shocking cruelty, the story is at its core a tender one, albeit sad and painful.

“I feel like I’m losing all my leaves,” Anthony confesses, “the branches in the wind in the rain.”

Even then—in his confusion and pain and helplessness, some truths still remain: The sun sometimes shines. Walks in the garden can still be pleasant. And he’s still cared for. He’s still loved. In his raging, growing darkness, there is still light.

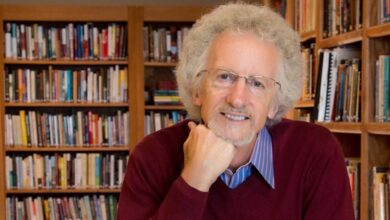

–Reviewed by Paul Assay