The collectivist horrors against Ukraine by Russia are unmatched in its history

During Ukraine’s long history, there have been no shortages of geopolitical manipulations against the Ukrainian people. Long before the current conflict, they can be seen in the Russo-Turkish Wars and Catherine the Great’s settling of German colonists among Ukrainian communities in order to displace local Turkish populations. Yet nothing compares to the early Soviet collectivist strategies which systematically and utterly changed the landscape of Ukraine, its society and its history.

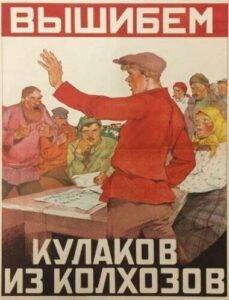

It all started with the same justification given today by Putin: state unity. Lenin, Stalin, and others wished for total military and economic control over the surrounding Slavic areas, in order to minimize the chances of rebellions by royalist sympathizers, pro-Western groups, or ethnic minorities who didn’t desire to be under the Soviet yoke. The early Soviet state enacted policies that pitted said groups against themselves, and made it appear as if the Bolsheviks were the heroes; Lenin was the one who brought prosperity and security to regions that have suffered under the totalitarian regimes of Russian Czars for centuries. One of these policies was Dekulakization: where well-to-do free peasants—or ‘kulaks’—were rounded up, expropriated, and deported to Siberian work camps and gulags. After the ousting of Czar Nicholas II, Lenin labeled these independent farmers and landowners as enemies of the state—an entire class opposing the will of the USSR and the tenants of Bolshevism. The communists couldn’t have a successful, independent class of laborers in one of the Union’s most fertile and prosperous regions; control was needed. In promoting the dekulakization, Stalin stated:

It all started with the same justification given today by Putin: state unity. Lenin, Stalin, and others wished for total military and economic control over the surrounding Slavic areas, in order to minimize the chances of rebellions by royalist sympathizers, pro-Western groups, or ethnic minorities who didn’t desire to be under the Soviet yoke. The early Soviet state enacted policies that pitted said groups against themselves, and made it appear as if the Bolsheviks were the heroes; Lenin was the one who brought prosperity and security to regions that have suffered under the totalitarian regimes of Russian Czars for centuries. One of these policies was Dekulakization: where well-to-do free peasants—or ‘kulaks’—were rounded up, expropriated, and deported to Siberian work camps and gulags. After the ousting of Czar Nicholas II, Lenin labeled these independent farmers and landowners as enemies of the state—an entire class opposing the will of the USSR and the tenants of Bolshevism. The communists couldn’t have a successful, independent class of laborers in one of the Union’s most fertile and prosperous regions; control was needed. In promoting the dekulakization, Stalin stated:

“In order to eliminate the kulaks as a class, it is necessary to openly break their spirit and resistance, and deprive them of the sources for further existence and development. The party’s current policy in the towns and villages marks a new procedure for eliminating the kulaks as a class.”

State-led propaganda was readily disseminated through Ukraine; propaganda of ‘greedy capitalist’ kulaks refusing to support their local communities and hoarding foodstuffs and winter rations spread like wildfire. Pogroms rose up and drove the free peasant class out of towns. In order to maximize the effects, Soviets threw the term kulak around liberally, where a farmer with just a couple of cows could be put in the same ‘kulak boat’ as a landowner with 5-6 more acres than his neighbors. The fast-and-loose definitions regulated by the State had countless individuals, regardless of their economic impact or personal successes, silenced and disenfranchised, just because Lenin decided so. Lenin signed the Hanging Order in 1918—a command to round up, dox, and kill people labeled as kulaks, writing:

Comrades! The uprising by the five kulak volosts must be mercilessly suppressed. The interest of the entire revolution demands this, for we are now facing everywhere the “final decisive battle” with the kulaks. We need to set an example.

-

- You need to hang (hang without fail, so that the people see) no fewer than 100 of the notorious kulaks, the rich and the bloodsuckers.

- Publish their names.

- Take all their grain from them.

- Appoint the hostages — in accordance with yesterday’s telegram.

This needs to be done in such a way that the people for hundreds of versts around will see, tremble, know and shout: they are throttling and will throttle the bloodsucking kulaks.

Telegraph us concerning receipt and implementation.

Yours, Lenin.

- Find tougher people.

Silence All Dissenters

Vigilante groups and Soviet battalions alike rounded up and deported any Ukrainian even suspected of acting against the State. Ethnic and religious minorities, and those who wished to preserve their Ukrainian heritage, rather than submit to Soviet culture and doctrine, were hunted down as well.

Since the Soviet Union worked hard to destroy evidence that pointed to the expulsion efforts, it’s difficult to know exactly how many people suffered under this policy. It is estimated that around 390,000-600,000 people died due to starvation, illness, and execution during the dekulakization of 1929-1933.

With the eradication of an entire economic class in Ukrainian society, the Soviets were free to take control of all agricultural and industrial processes in the area. Wide sweeping dictacts championing collectivization and fealty to the state resulted in Soviet-run farming communities called ‘kolkhozes.’ In accordance with Bolshevism, the means of production were to benefit the state, not the individual. State-run farms liquidated all assets, controlled grain supply, and only paid their farmers in grain rations, not currency. Landowners and farmers were forced to give their yields to regional officials, where it was then dispersed back to the populace. The Ukrainian people—being made up of mostly agriculturalists at the time—were completely dependent on the Soviet State for sustenance and security.

Collectivization in Practice

The summary disappearance of a massive segment of Ukrainian agricultural society quickly led to a man-made famine which affected the vast majority of the Soviet Union. State control over grain supply resulted in the inadequate distribution of food to the Ukrainian and Caucus regions; most of the collectivized food went to fuel the Moscow and St. Petersburg metropolises.

What came next has been labeled one of the worst atrocities of modern history: Holodomor. In just one year (1932-1933) a great famine occurred in Ukraine which stole 3.3 to 5 million lives. The Court of Appeal of Kyiv recently found that the lives lost during Holodomor may have been closer to 10 million.

Primary sources of the Holodomor account for the daily struggle and unspeakable horrors Ukrainians experienced. Fedir Burtianski, a laborer who set out to find work in the Donbas mines, recounted the time he witnessed the trial of two brothers and their father who were accused of committing cannibalism. He recounted one of the accused stating:

“He said, ‘Thank you to Father Stalin for depriving us of food. Our mother died of hunger and we ate her, our own dead mother. And after our mother we did not take pity on anyone. We would not have spared Stalin himself.'”

For Stalin, the deaths were just a statistic. His regime quickly replaced the depopulated region with Russian laborers. The industrial growing areas of Donetsk and Luhansk saw an influx of Russian colonists, as did the Crimean Peninsula, which acted as one of the USSR’s warm-water ports—a crucial military and trade component. The cruel and impersonal relationship between occupying Soviets and the native Ukrainians is evident throughout the existence of the USSR: from Lenin’s collectivization all the way up to Chernobyl, where Soviet officials cared more about containing the explosion and protecting Moscow than taking preventative actions that would have prevented the accident from happening in the first place.

For the USSR, its people—whether in the Moscow metropolis or the Ukrainian lowlands—were seen as a means to an end; they were numerous cogs in the regime’s machine, rather than individuals with civil and political rights. The people of Ukraine were held at the mercy of Lenin, Stalin, and others; they were powerless in every sense of the word. With no recourse to preserve their way of life and means of production, they were subservient to an entity that had control over all; one which not only decided the fate of millions of Ukrainians but also merely blinked at the famines they created and brushed them off stating that it was all for the security and proliferation of the greater Soviet Union.

–ByConnorVassile | Foundation for Economic Freedom