West Side Story is refreshing in faithfulness to 1950s Broadway

West Side Story is an old story. Really old.

It’s based on Shakespeare’s classic tale of star-crossed lovers, Romeo & Juliet, replacing the warring Italian clans of the Montagues and Capulets with the Jets and Sharks. It was a massive hit on Broadway back in 1957, and it got even bigger when it moved to the screen in 1961. Featuring Rita Moreno, Richard Beymer and Natalie Wood (who didn’t sing a note), the first film version of West Side Story won 10 of the 11 Academy Awards it was nominated for and was the highest-grossing film of the year. The American Film Institute ranks it as the second-greatest musical ever made—just behind Singin’ in the Rain.

So why make another?

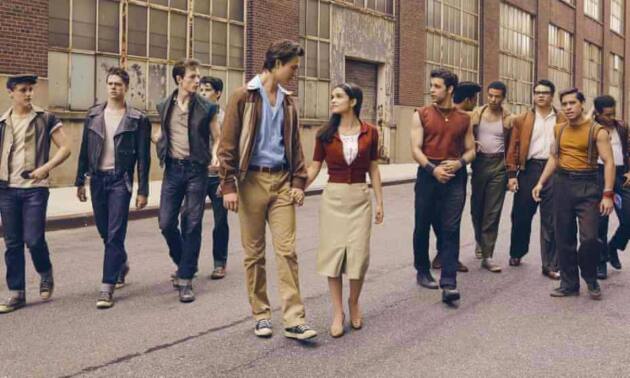

The cast, which sings all of their own songs, includes Rachel Zegler (Maria), Ansel Elgort (Tony), Ariana DeBose (Anita), David Alvarez (Bernardo), Mike Faist (Riff), Josh Andrés Rivera (Chino), Corey Stoll (Lietenant Schrank), and Brian d’Arcy James (Sergeant Krupke). Rita Moreno, who won an Academy Award for her portrayal of Anita in the 1961 film. Academy Award-nominated screenwriter and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tony Kushner (Lincoln) is behind the script.

Director Steven Spielberg says that the soundtrack for West Side Story was “actually the first piece of popular music our family allowed into the home,” according to Vanity Fair. “I … fell completely in love with it as a kid.” He also told Yahoo that the musical—what with its issues of racial and ethnic strife, feels quite timely, “more relevant to today’s audience than perhaps it even was in 1957.”

America’s been called the great melting pot. But sometimes, that pot boils over.

So it is in the mid-’50s on New York’s toughest streets. Crumbling neighborhoods are making way, block by block, for gleaming new apartments. Traditional Irish conclaves are becoming multicultural communities. And the Jets don’t like that one bit.

Riff insists the lily-white Jets are determined to defend their turf ’til the last brick tenament takes a wrecking ball to the gut.

The neighborhoods’ burgeoning Puerto Rican population, though, aims to make a home on those same streets—and those immigrants aren’t about to be pushed around by a bunch of thuggish Irish delinquents. Puerto Rican youth have created a gang of their own, called the Sharks. And if the Jets push them, the Sharks will push back—and push hard.

The rival gangs are on a collision course, and both can’t wait for the crash. At a dance held at the local high school—a dance designed to foster a little peace and even friendship—Riff’s ready to drop the gauntlet. But at that same dance, across the gym, a boy sees a girl. The girl eyes him back. And slowly, the two edge across the floor and meet behind the bleachers.

The boy, Tony, has indeed been a Jet from his first cigarette. He and Riff formed the group, and during the gang’s last all-out rumble—against a group of Egyptians—Tony nearly beat another guy to death. That little incident got him sent to prison for a good long while, and gave him a chance to think for a good long time. He’s been wondering whether life might have bigger plans for him.

But when he meets this beautiful Puerto Rican girl, he wonders no more. He knows.

Maria is just 18 but already set up with Chino, a smart guy who fixes adding machines. But while Chino is nice and all, she’s not crazy about him. The gringo she’s eyeing now? He’s different.

But do an Irish bad boy and a Puerto Rican good girl have a chance in this crazy, mixed-up world?

Tony’s time in jail made him a better person—more aware of his own weaknesses and the dead-end direction his life was heading. When the movie opens, he’s severed most of his ties with the Jets, and he works honestly as a clerk for Valentina (an elderly woman who now runs her late husband’s drug store). And when Tony meets Maria, viewers get the sense that the whole trajectory of his life might change—where he’ll be living not just for himself, but for someone else, too. (That sense of commitment and devotion is echoed by both young lovers in the song “one hand, one heart,” where they pledge, and almost pray to “make of our lives one life.”)

Tony probably couldn’t have done as well for himself without Valentina, played by Rita Moreno who won an Oscar for her role in the 1961 film. She gave him a job, a place to stay and offers some pretty cogent advice, too. And she, out of everyone, is willing to help Tony and Maria get a fresh start. You get the sense that if everyone in the neighborhood listened to Valentina, things might’ve gone much, much better.

While Valentina’s advice doesn’t rest on the spiritual, there are some spiritual elements to the story. On a date, Maria and Tony spend time in a very church-like room—complete with stained glass and statues of angels—where Maria kneels before an altar and encourages Tony to kneel with her. The two engage in what amounts to a self-officiated wedding there—sanctifying their love in a surprisingly traditional way before God.

That’s the most explicitly religious moment in the musical. But West Side Story’s edges are tinged with spirituality throughout—from the cross hanging above Maria’s bed to faith-inflected dialogue and song lyrics when Tony sings that Maria’s name is “almost like praying.” The Puerto Ricans we see seem firmly, if imperfectly, tied to the Catholic Church.

West Side Story is built on racial and ethnic tensions between migrants and descendants of migrants very much a part of New York in the 1950s. Though the characters’ biases are never lauded, they’re still quite obvious and, frankly, inescapable.

West Side Story shows all of the tensions of a migrant neighborhood unlike the original play or movie. It dispels a longstanding notion that many of us have: that classic musicals are squeaky-clean relics of a more innocent age.

This new version doesn’t deviate much from the original West Side Story. Where it does deviate, it gets rougher.

But the end product is surprisingly—even refreshingly—traditional. It adheres closer to the original Broadway production than the 1961 film, and it feels, top to bottom, like an old-fashioned musical where people burst into song for no reason. That’s not a bad thing.

–PaulAsay | PluggedIn