How rethinking church properties could help save dying congregations

Rome, Georgia, features steeple after steeple defining its skyline. Its tourist map for Rome depicts 15 churches in its six-block long, four-block-wide downtown area alone. The church properties take up a substantial portion of developable land downtown while their congregations shrink.

Like many cities nationwide, most of Rome’s congregations are dwindling. The religious and social forces behind the exodus are complex, but their impact is unmistakable. Many of America’s houses of worship, with congregations too small to maintain their own properties, are calling it quits. Some sell their properties to the highest bidder. Other properties in less affluent areas sit vacant for years. Still others lease surplus property to other entities. A few partner with developers to reconceptualize facilities and land while maintaining a smaller house of worship onsite.

What closed department stores have been to downtowns over the past 30-40 years, emptying houses of worship will be over the next three to four decades. Pre-pandemic estimates were that 75 to 100 houses of worship were closing per week, or 3,750 to 7,500 per year. America now may be looking at the closing of as many as 100,000 houses of worship — more than a quarter of the estimated total — over the next few years.

It’s not a new idea. Church Executive magazine encouraged pastors to consider it in 2009 – long before the pandemic.

In major cities with hot real estate markets, developers chomp at the bit to rush in, buy property, and redevelop it into luxury condos or Class A offices. In America’s heartland, there’s no such rush — just a shrewd picking over of the best redevelopment opportunities and leaving the rest to go fallow in the landscape.

Challenges and barriers

Many factors can foil the successful reuse or redevelopment of a house of worship:

Real estate. The designs that make a house of worship captivating — soaring ceilings, ornate decorations, old-fashioned infrastructure — can make it difficult or expensive to revitalize as residential, commercial or retail space. Environmental problems — asbestos, black mold, lead pipes, buried oil tanks — can add to problems and costs. Deed-related issues, such as abutting graveyards or reversion clauses — awarding the property back to the original donor in the case a house of worship is no longer operating onsite — can kibosh an otherwise well-developed plan.

Faith institutions. Congregations tend to be nostalgic about the past; cold, hard facts may not always carry the day. The lines of authority of religions and denominations can be confusing; some make decisions top-down, some bottom-up and others a confusing combination of the two. Divinity schools do not train clergy in business or real estate; clergy want to spread the good word, not act as the Grim Reaper.

Communities. A municipality can have zoning and code regulations that make it difficult if not impossible to turn a single-use house of worship into a mixed-use development, especially one involving affordable housing. Neighborhood associations can be a drag on new ideas as well. Local finance officials, hungry for revenues, often swoop in as soon as a house of worship is closed to levy large property taxes against an empty house of worship, adding to a project’s financial burdens.

Resources. In small- to mid-size municipalities and lower- to middle class neighborhoods, the market may not fully support a chosen project, and it may require significant capital and/or operating subsidies. Competition for such subsidies can be fierce. In addition, such a project may require an experienced developer who is familiar with the intricacies of reusing and redeveloping houses of worship.

Opportunities and benefits

The best hope that most rundown houses of worship properties have of being revitalized, including their parking lots, is to host a mix of uses. Sanctuaries built for hundreds of congregants can be shared or downsized. Auxiliary buildings, kitchens, educational facilities and parking lots can be repurposed for housing, while commercial and retail uses can be brought into the mix to offset the costs of construction, maintenance, utilities and insurance. The property can pay its share of property taxes and be used 24/7 instead of for a few hours once or twice a week.

In “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” urban guru Jane Jacobs outlines four major attributes that make for a great city: mixed-use, walkability, old buildings and density. Houses of worship may be old, but most have none of the other three attributes. Most are single-use; they act as “beached whales” amid the urban fabric — large, low-density pieces of property with fences, large parking lots and most doors locked shut. Turning a house of worship into a mixed-use, walkable, higher-density property can help restore life to a community, while targeted adaptive reuses, developed in conjunction with stakeholders, meet prioritized community needs.

Strategies for transition

There is no magic potion to drink to guarantee a successful initiative. The process requires constant attention to multiple issues of real estate, faith institutions, communities and resources. Concentrate on one at the expense of the others at your peril. Here’s some data to collect.

Real estate:

- Size and condition. Square feet and acreage, number and types of rooms and types of rooms, accessibility, utility and insurance costs, flood/disaster zones. When was it built and renovated? Are major repairs or capital replacement needed?

- Value. Consider contracting for a professional appraisal, with all three approaches: comparison (what a similar property would sell for), income (property revenues) and replacement cost (what it would cost to rebuild).

- Land use. Zoning, historical preservation protections, rental agreements with other congregations or other institutions. Deed restrictions. Is the property affected by any plans, e.g., the city’s comprehensive plan? What are the qualities of the neighborhood? Is it walkable and mixed-use?

- Real estate market. What is the real estate market for housing, office and commercial? Is another house of worship looking for space like yours — either to own or to share?

Faith institutions: Who are the key decision-makers in the congregation and how willing are they to change? How does the congregation make decisions? What are the attitudes for changing the property use? Does the religious institution make decisions top-down, bottom-up or a combination of the two?

Communities: How do the mayor, district council member, city manager, planning director and preservation board feel about a potential project? What is the process? Does your house of worship have relationships with the aforementioned officials? What do the property’s neighbors want, and can a feasible plan be developed that they can support?

Resources: Not every community has access to developers experienced at reworking houses of worship. Look into developers and real estate professionals that will be needed throughout the project’s life cycle. What grants, loans or other resources are available? If the project includes low-income housing, multiple funding sources will likely be required.

Role for new urbanists

The opportunity is ripe for applying the Congress for the New Urbanism’s culture and methods to the reuse and redevelopment of houses of worship. The CNU Member’s Christian Caucus, working with other interested CNU members, accepts this challenge.

A particular need is to revamp zoning and building codes. Work has already begun in this area. Duke Divinity School’s Ormond Center is working with the Project for Lean Urbanism to adapt the Pink Zone Manual for areas where multiple churches are undergoing redevelopment. Making Housing and Community Happen, a faith-based organization, is proposing “congregational land overlay zones” to support the development of housing on church properties in California. New Urbanists also can build on the work of Partners for Sacred Places to inform, shape and contribute innovations in the historic preservation of houses of worship.

New urbanists should conceptualize radical new models for houses of worship. Single-use is out; mixed-use is in. Sidewalk-deadening walls, locked doors and fences are out; enlivened and enlivening uses are in, including pocket parks and gardens. Empty voids with vast parking lots used one or two days a week are out; dense developments used 24/7 are in. We urgently need new configurations that faith institutions can model and experiment with.

Conclusion

What will happen to the 15 church parcels in Rome’s small downtown may determine the city’s success over the next 30-40 years. Rome is one of thousands of cities, towns, villages and neighborhoods facing the disruptive storm of closing and closed houses of worship.

New urbanists need to build bridges with faith communities to reuse and redevelop houses of worship.

As tens of thousands of faith buildings on hundreds of thousands of acres move into transition, the need is urgent. New urbanists could play a key role in bringing real-estate professionals, faith institutions and municipalities together to work on the problem.

As Church Executive wrote, “Mixed-use is a tool for developing diversity, creating a more vibrant livable community that is resource to the entire area. In short, an integrated, mixed-use church master plan can be a vital and relevant bridge to the community both now and in the future.”

This article was first published at cnu.org.

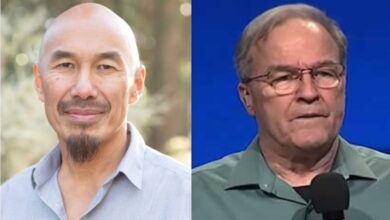

Rick Reinhard is principal of Niagara Consulting Group and associate with The Lakelands Institute. After 25 years leading community economic development and local government organizations in Buffalo, Atlanta, Washington and Northern Ireland, he served the last five years in executive roles with the United Methodist Church. He was a Loeb Fellow at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. He may be reached at richardtreinhard@gmail.com.

Chris Elisara, Ph.D., is the founder of the Creation Care Study Program, Center for Environmental Leadership and the award-winning production company First+Main Media