Christian History: Bible backing archaeologist Kenyon

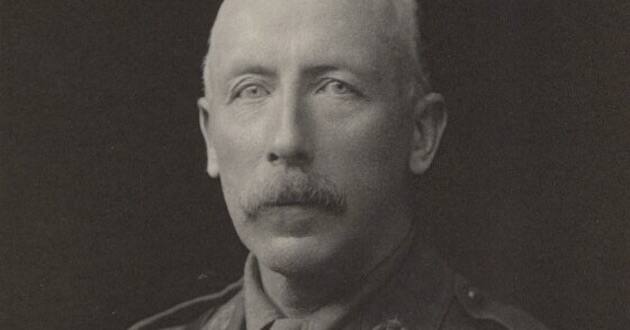

Seventy years ago this month, Frederick George Kenyon passed away. He was a trailblazer in biblical archaeology.

“Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established.”

Frederick George Kenyon was in an authoritative position to write those words. After graduating from Oxford University (where he also tutored), he went to work for the British Museum in 1889. Nine years later he had become assistant keeper of manuscripts. By 1909 he was its director and head librarian. A renowned scholar of ancient languages, he also took a deep interest in the Bible.

His position offered him many opportunities to study ancient papyri in the Greek language. Papyri are documents written on Egyptian reed “paper.” He showed that there are parallels between things written in Greek documents and the text of the Bible.

Scholars as great as Kenyon often write in such a way that few people can follow what they say. But Frederick had a gift for making his words understandable to ordinary people. He wrote books such as Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts. He was convinced that science does not disprove the Bible, but rather supports it.

Kenyon concluded from his research, “The Christian can take the whole Bible in his hand and say without fear or hesitation that he holds in it the true Word of God, handed down without essential loss from generation to generation, throughout the centuries.

Writing about the Bible, he showed that our documentary evidence for it is very good compared to the documentary evidence for other events in ancient history. For instance, here is what he has to say about Sophocles: “We believe that we have in all essentials an accurate text of the seven extant plays [plays for which we still have copies] of Sophocles; yet the earliest substantial manuscript upon which it is based was written more than 1,400 years after the poet’s death.” By comparison, the oldest manuscripts of the New Testament date just decades after the death and resurrection of Jesus and almost every verse of the New Testament had been quoted in a writing by someone somewhere by the third century.

“The number of manuscripts of the New Testament, or early translations from it in the oldest writers of the Church, is so large that it is practically certain that the true reading of every doubtful passage is preserved in some one or other of these ancient authorities. This can be said of no other ancient book in the world.”

Kenyon concluded from his research, “The Christian can take the whole Bible in his hand and say without fear or hesitation that he holds in it the true Word of God, handed down without essential loss from generation to generation, throughout the centuries.”

In 1920, Sir Frederick became president of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. He had been knighted in 1912. Between 1933 and 1936, Kenyon published the famous Chester Beatty papyri in five volumes. The British Museum had acquired these. They dated from about 200 AD and included most of the Epistles of Paul.

Kenyon was not only interested in the Bible, but in the era of Aristotle and the poetry of Robert Browning. The great scholar died August 23, 1952. He was 89 years old, but had lived long enough to learn of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Bibliography:

“Kathleen Mary Kenyon.” http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/information/ biography/klmno/kenyon_kathleen.html

Kenyon, Frederic G. The Bible and Archaeology. New York, Harper, 1940.

Various encyclopedia and internet articles, such as “Kenyon” in Encyclopedia Americana, 1956.

–by Dan Graves