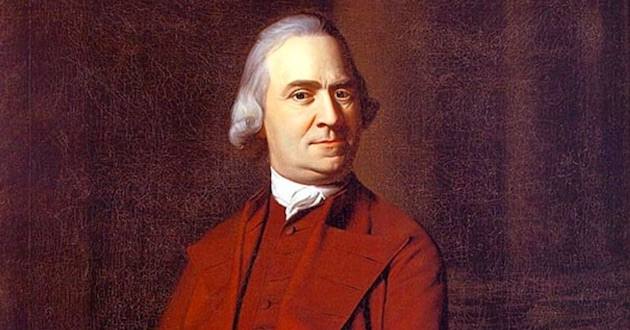

Samuel Adams, Father of the American Revolution

Samuel Adams was one of the earliest and most effective of the Founding Fathers in building support for independence and in generating opposition to every British provocation. Those activities earned Adams the title “Father of the American Revolution.”

The prospect of going to war against the British Empire, an established military and economic world power, looked like a David vs. Goliath situation, and there was much to support that characterization. Like Israel’s King David, the American Founders had faith that their cause was just and that God would give them the victory over a much stronger adversary.

The dynamic role Adams played in the independence movement was understood by British leaders to the point that General Thomas Gage, in an effort to end hostilities with the Colonists before they began, offered pardons to all rebels except for Adams and John Hancock “whose offenses are of too flagitious nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment.”

READ: Noah Webster: what you don’t know

On another occasion, in response to a British pardon initiative, Adams said, “I am told that Lord Howe has lately issued a Proclamation offering a general pardon with the exception of only four Persons viz Dr. Franklin Coll, Richard Henry Lee, Mr. John Adams, and myself. I am not certain of the Truth of this Report. If it be a Fact I am greatly obliged of his Lordship for the flattering opinion he has given me of myself as being a Person obnoxious to those who are desolating a once happy Country for the sake of extinguishing the remaining Lamp of Liberty, and for the singular Honor he does me in ranking me with Men so eminently patriotick.”

Adams first began to attract the attention of those in charge of governing the colonies in 1764 when he took a strong public stand against enforcement of the Sugar and Molasses Acts which imposed shipment restrictions and high taxes on those commodities.

Adding fuel to the fire in 1765, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act which required a tax stamp on all legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards. This tax was denounced as “taxation without representation,” an effective rallying cry that influenced many to join the movement for independence. Formed to oppose the Stamp Act in 1765, the Sons of Liberty, a patriotic society, made it difficult if not impossible, through a campaign of physical violence, to distribute the stamps.

The Sons of Liberty were also successful in adapting and utilizing another very effective tool in uniting the Colonies. Called “Committees of Correspondence,” a number of chapters had been established years earlier as a way for Colonial legislatures to communicate with each other, but now they became essential in shaping public opinion and for building united opposition to British rule. The Committees of Correspondence provided the colonists with an effective way to develop a unified policy of resistance. Adams emerged as a prominent participant as leader of the Boston chapter.

Adams extensive writings made him one of the best known of the persistent promoters of the call to revolution. Most of his revolutionary writings appeared originally in The Boston Gazette, a large circulation newspaper for its time, in which he expressed this tenet of the revolution: “The right to freedom being the gift of the Almighty…The rights of colonists as Christians…may be best understood by reading and carefully studying the institution of The Great Law Giver and Head of the Christian Church, which are to be found clearly written and promulgated in the New Testament.”

Adams also led opposition to the Townshend Acts that taxed imports of a number of commodities, including tea, and, on December 16, 1773, instigated the event known as The Boston Tea Party. Under cover of darkness, a group of agitated citizens, many of whom had disguised themselves as Mohawk Indians, boarded three British ships docked in Boston and dumped an estimated 300 chests of tea into the harbor.

A few months later, on September 5, 1774, Adams was elected a delegate to the First Continental Congress. That body became the de facto American revolutionary government. Colonial leaders had become convinced provocations by the mother country demanded unity if the Colonies were to successfully counter British attempts at further subjugation. The First Continental Congress was an im;ortant step in that direction.

Passage by the British Parliament of four laws designed as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, known by the Colonists as the “Intolerable Acts,” provided the impetus for convening the congress. The four punitive acts were the Boston Port Act which closed Boston to trade; the Massachusetts Government Act which revoked the Colony’s charter; the Quartering Act which required Colonists to provide quartering for British soldiers; and the Impartial Administration of Justice Act which removed British officials from the jurisdiction of Massachusetts courts.

Prior to adjournment of the First Continental Congress, the delegates called for a second congress to be convened May 10, 1775, if the British persisted in their “Coercive Acts,” another popular name for the Parliamentary measures they considered to be intolerable. Prior to that date, the die had been cast by a number of events including the April 19, 1775 battles of Lexington and Concord involving British soldiers and American “minutemen,” the name given to the Colonial militia who pledged to fight “at a minute’s notice.”

The Second Continental Congress was convened as scheduled with Adams again serving as a delegate. The primary responsibilities of the congress were to formulate and oversee the conduct of the war, to advance and preserve the newly formed union of the 13 colonies, and to develop a constitution of sorts to guide the emerging independent country. George Washington was commissioned to organize and command a continental army. Committees were established to generate plans for the conduct of international trade, develop fiscal policies, and to find ways to seek much-needed military and financial assistance overseas.

Developing a constitution proved to be difficult with agreement on the Articles of Confederation finally being achieved November 15, 1777. It took more than three years from the time it was approved by the congressional delegates for the colonies to officially ratify it. In the meantime, Congress approved the Declaration of Independence July 2, 1776 and formerly adopted it on the Fourth of July. At the signing of the Declaration, Adams said: “The people seem to recognize this as though it were a decree promulgated from heaven.”

In 1788, Adams played a major role in the ratification of the U.S. Constitution by the state of Massachusetts. In 1789 he was elected lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, and governor in 1794. He died October 2, 1803.

That he was a man of character, steadfast in his Christian faith, is clear from the life he lived and many of the memorable words he spoke, especially on the importance of public morality: “A general dissolution of principles and manners will more surely overthrow the liberties of America than the whole force of the common enemy. While the people are virtuous they cannot be subdued; but when once they lose their virtue they will be ready to surrender their liberties to the first external or internal invader…If virtue and knowledge are diffused among the people, they will never be enslaved. This will be their great security.”

History’s rewriters have, for the most part, ignored Samuel Adams because it would be difficult indeed to twist these words that were included in his will: “Principally, and first of all, I resign my soul to the Almighty Being who gave it, and my body I commit to the dust, relying on the merits of Jesus Christ for the pardon of my sins.”

Some history revisionists have referred to the founders most outspoken about protecting religious freedom, including Adams, as being “radical” as a way of attempting to create the impression that people who today are concerned about religious freedom and traditional Christian beliefs are on the fringe.

To some of his contemporaries, he was known as “the last Puritan.” Puritan has become a pejorative term in the vocabulary of neo-liberals who would mislead their fellow citizens regarding the rich Christian heritage of the United States of America.

–Bob Gingrich is a Kansas City author, historian on the founding of our nation, and Metro Voice contributor.

You can support Metro Voice because we’re an Amazon Affiliate. Learn more about Mr. Gingrich’s book on America’s heritage, other books and resources you might enjoy below.

Check out one of Noah Webster’s most famous books, Advice to the Young.

As an Amazon Affiliate, your browsing helps support Christian journalism.