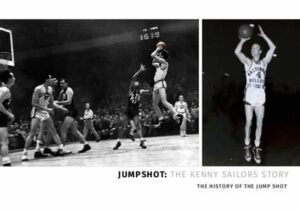

He needed to be taller than his big brother. He needed to fly. He would invent the jump shot as we know it.

Back then, in the 1930s, the game of basketball was bound by gravity. Coaches told players that to jump was a surefire way to lose control and lose position. Keep both feet on the ground, they said. Take two-handed set shots, they said. That meant to be good, you had to be big. Basketball was no sport for short guys.

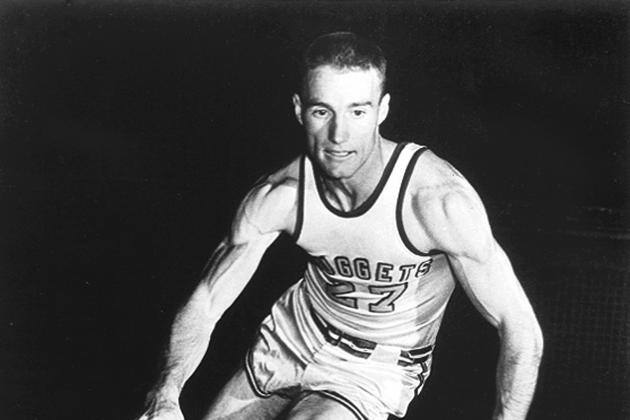

But where Kenny Sailors grew up, on a farm near Hillsdale, Wyoming, basketball was the only real game in town. And his first real opponent — his big brother, Bud— was 10 inches taller than he was. When you love basketball but you’re only 5 foot 7, you’ve got to get creative.

HOME RELEASE DATE: April 16, 2020

DIRECTOR: Jacob Hamilton

DISTRIBUTOR: One Spark Films

REVIEWER: Paul Asay

So he jumped. And he shot. And lo and behold, the ball went straight in the basket.

READ: Stephen Curry discusses faith amid pandemic

“I was surprised as he was,” Sailors admits.

And so began the curious and almost entirely unknown odyssey of basketball’s least-known legend, and a life that would take him to a college national championship, the NBA, World War II and the Alaskan wilderness.

This documentary argues that Sailors created the modern jump shot — the shot that forms the cornerstone of basketball today, a shot emulated and perfected by such NBA superstars as Stephen Curry (who serves as the film’s executive producer) and Russell Westbrook, among myriad others.

But more than that, this film chronicles the lifelong journey of a man who loved a sport — but loved other things more: his wife. His family. And God.

“I know that I belong to the greatest hall of fame that any man or woman can ever belong to,” Sailors says. “And when you belong to that, and you know you belong, you don’t worry about the halls of fame that men create down here. Don’t mean that much to you.”

After all, there’s more than one way to fly.

Kenny Sailors’ story would be pretty remarkable even if the guy was a jerk. But instead, we get an honest-to-goodness role model. Throughout Jump Shot, we see how grounded (figuratively speaking) Sailors was. Indeed, perhaps one of his most remarkable chapters takes place when his playing days were done.

After playing in the NBA for several years — making around $7,500 a season, he says — Sailors left the sport. He and his family left for the wilds of Alaska. Sailors and his wife, Marilyn, would spend the next 35 year there. They made the move in part because of Marilyn’s health: She suffered from asthma, and the doctors thought that if she got away from the crowded, polluted cities, she might live past the age of 50. So they homesteaded out there and eventually became fixtures in the tiny community of Glennallen.

Sailors coached about every sport there was to coach at Glennallen High School, but he made his biggest mark in girls’ basketball. Back when he started, girls’ basketball had a different set of rules: Only certain players could run the full court, because it was thought that a full-court game would be too taxing for the young women.

Sailors helped change all that, and he coached his girls’ b-ball teams to three state championships in seven years. He encouraged native American teens to play, too, even though other teams discouraged their participation (because they tended to be a bit shorter). And he wasn’t, according to some, all that concerned whether his players were even that talented: Sailors believed lessons learned on the court would benefit these women later on.

“I was a really lousy basketball player,” one former participant, Rose Tyone, recalls. “But he encouraged me to play.”

One of Sailors’ friends recalled how during the NCAA’s Final Four, Sailors rattled off his own final four — the things most important to him. “God, husband, father and U.S. Marine, in that order,” he reportedly said. Basketball didn’t even make the list.

And yet, we see Sailors on the court at age 91 — shooting baskets and moving like a healthy man of 60. That’s pretty positive, too.

Also impressive is the young man’s faith.

Jump Shot doesn’t make a big deal of Kenny Sailors’ Christian convictions, but that faith is clearly important to him. It does, however, include him speaking on his faith.

“The Lord has shown me that there’s a lot of things more important than sports or basketball,” he says, and his life is proof of that. When he speaks about a period of difficulty, he says, “It’s tough, but the Lord gives you strength that you don’t even know where it comes from. He gives you the strength to go through most anything.”

March Madness invented?

When Kenny Sailors won his NCAA championship with Wyoming back in 1943, there was no such thing as March Madness. Indeed, the sport itself was still young. “It looked almost like a different sport back then,” says former NBA superstar Dirk Nowitzki in the documentary.

And then came Sailors.

Others might claim to have “invented” the jump shot, this documentary tells us. Sailors himself admits as much. Any kid who threw the ball toward the basket while hopping a bit in the 1890s could rightfully claim to be the real inventor, he tells us.

But the jump shot as we know it today — a straight, vertical jump combined with a one-handed shot — seems to be Sailors’ own. And you look at pictures of him taking the shot and transpose them beside more contemporary greats — Durant, Curry, even Michael Jordan and Larry Bird — and you can see the remarkable imprint of Sailors’ influence.

But Jump Shot does more than fulfill a basketball craving. It gives us a picture of a man who seems to deserve the title of hero — not because he was a great basketball player (though he was unquestionably that, too), but because he was a great, God-fearing man.

Well-crafted and well-told, this movie serves as more than a balm for this difficult time: It’s a bit of an antidote, too. It reminds us that difficulties and obstacles will always be a part of our mortal journey. But with perseverance and creativity, we can find a way through them, or around them, or in Sailors’ case, over them.

We can jump.