The Jewish celebration of Passover, which began this past Saturday and continues through April 20, carries profound meaning not only for Jews but also the Christian who seeks to understand its rich traditions. The holiday’s significance extends beyond its historical roots, as Jewish communities maintain heightened vigilance during this sacred time.

Passover in the Bible originates from the book of Exodus when God instructed Moses and Aaron and the Israelite people in Egypt to mark their houses with the blood of a lamb so that the Lord would “pass over” their house and spare their firstborn son.

God’s instructions about the Passover appear again, with details about how to observe it once the Israelites had left Egypt, in other parts of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible). These include references in Numbers 9:1-4, Numbers 28:16-25, Deuteronomy 16:1-6 and Leviticus 23:4-8. These other references show that God did not intend the Passover as a onetime event but an annual feast in which the Israelites would remember how God had saved them.

But Passover is more than just a historical remembrance. According to Rabbi Jerry Feldman of Adat Yeshua, it is inextricably linked to another significant event: the giving of the Torah on Mt. Sinai fifty days later. “Passover and Shavuot are bookends representing one story; they comprise a single redemptive narrative from Redemption (the deliverance from Egypt) to Revelation (the giving of the Torah),” says Rabbi Feldman.

This connection is often missed by Christians, Rabbi Feldman notes, recounting a consistent experience over his 44 years of speaking in churches. “When given the opportunity, I have asked the audiences a question that’s only been answered correctly once. ‘What happened 50 days after the first Passover in Egypt?'” The answer, of course, is the giving of the Torah, but the question is usually met with silence.

Passover (or Pascha) sanctified Israel’s time and life as a sign pointing them to the coming incarnation of Jesus. In this feast, they were to remember him and what he did for them in delivering them from Egyptian bondage. But more importantly, it pointed them to his coming in the flesh. When John the Baptist saw Jesus, he told his followers, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29). The Israelites were to know him in the blood of a slain lamb, a sign pointing to him as the Lamb of God. Yet when he became incarnate as this lamb, they did not recognize their own Lord who had delivered them from Egypt (John 1:11).

In the gospels, Jesus came at least twice to Jerusalem to observe Passover. He came at the start of his ministry when he cleared the temple and declared that if the temple was destroyed, he would rebuild it in three days (John 2:13-22). When Jesus came the next time, riding into Jerusalem on a donkey, he and his disciples got a private room for observing Passover.

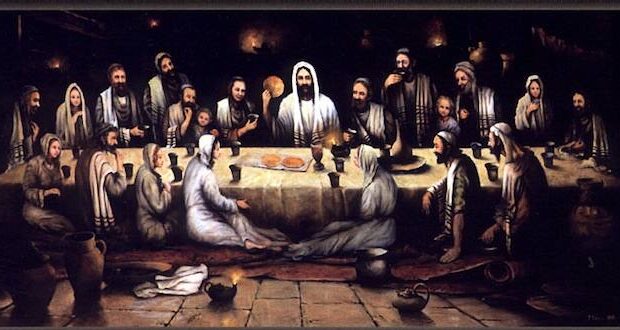

When Jesus and his disciples had the Passover meal in Jerusalem, he took the wine and bread (items that were supposed to be eaten at particular times with particular words spoken over them for the Passover proceedings). Instead of speaking from Exodus 12 or talking about the Israelites slaying a lamb in Egypt, he did something different:

Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and after blessing it, broke it and gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink of it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (Matthew 26:26-28)

By saying these words, Jesus claimed something about himself that shifted how his followers saw Passover: he claimed to be the Passover lamb. This theme continues in the later books of the New Testament, particularly the epistles.

Rabbi Feldman highlights the significance of Shavuot (Pentecost) in Acts 2, emphasizing that it was “the commemorative day for celebrating the giving of the Torah through Moses to establish the constitutional identity of the nation of Israel.” He provocatively states, “Acts 2 is a Jewish holiday!” and challenges the common Christian understanding of the event. “In fact, if what you presume when you use the label Christian is a non-Jewish Christ-follower, there is not a single Christian in all of Acts 2.”

The giving of the instructions of God, whether for Jew or Gentile, was an act of God’s grace which no one earned or deserved. Paul said, “So, then, the law is holy, and the commandment is holy, righteous and good” (Rom7:12).

Rabbi Feldman encourages Christians to recognize the Jewish roots of their faith and to appreciate the continuity between the Old and New Covenants. He concludes, “I trust that this year Shavuot (the Day of Pentecost) will not just be a day to recognize what happened in Acts 2, but a day filled with powerful desire for the presence of God to confirm in us that we are the children of God destined to fulfill his glory presence purpose on earth until He comes! I will, likewise, but for me it will be Shavuot in Messiah!”

–Dwight Widaman | Metro Voice

Metro Voice News Celebrating Faith, Family & Community

Metro Voice News Celebrating Faith, Family & Community