Every few years I return to the biblical Book of Job, the best guidebook I know for dealing with suffering and loss. It’s an ancient work with timeless applications.

I’m not sure why I’m bringing Job up again. Maybe it’s the war in the Middle East with its accompanying photos of distress. Maybe it’s the local stories I’ve heard of fatal car wrecks and life-threatening cancers. Maybe it’s just the daily toll of age and oncoming frailty.

Whatever the reasons, Job has been on my mind. If you haven’t read the book lately — or ever — it’s worth checking out, even if you don’t consider yourself spiritual.

In the story, Job is a wealthy man with a big heart and a big family. He’s done everything right.

Then, suddenly, disaster strikes. His 10 children die. His crops fail. His health collapses. He’s left lying in the dust, in agony.

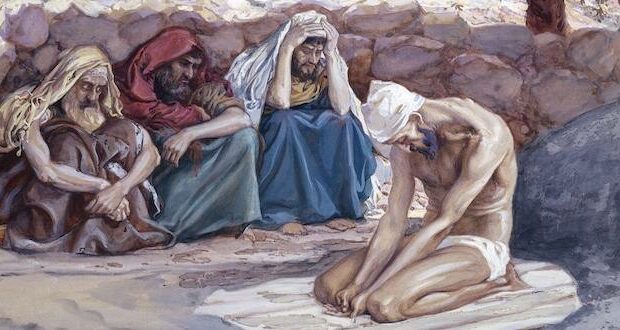

His friends come to visit. When they see the state into which Job has fallen, they wail, then plop in the dirt beside him. They sit there seven days, too sad to speak.

But Job curses his mother for having given birth to him. He rages at God for not having the decency to let him die now. Job’s friends are so alarmed by his attitude that one of them, Eliphaz, springs to God’s defense. Job gives Eliphaz a piece of his mind.

Another friend tells Job off. This cycle continues. Job’s friends trot out every religious bromide known to humanity. They warn Job never to speak ill of God. They claim God is always gracious, always fair. They say Job must have committed secret sins he’s being punished for.

The longer they bloviate, the angrier Job gets. He insists he’s done nothing wrong. God is absent or unfaithful. Job shakes his fist and demands that the Lord explain himself.

Finally, God does speak. But all he offers is a non-answer answer. He says, I’m God and you’re not, and you wouldn’t understand even if I told you.

Significantly, God congratulates Job for telling the truth and not mouthing ridiculous tropes as his friends do. And then, he orders Job to forgive and pray for those same idiot friends.

For those who have neither the time nor the inclination to read the book for yourself, here are my takeaways. These points are as valid today as they must have been 2,500 years ago:

- If your friend is going through something gawd-awful, just show up and sit with her. Practice the ministry of presence. It’s a comfort to suffering folks.

But keep your lip buttoned. Trying to tell people why they’re suffering does nothing but multiply their pain. Fact is, you don’t know why they’re suffering. So don’t fill the silence with baloney. And even if you think you do know why, it’s nearly always better to keep that to yourself.

- This is related to the previous point. If you’re with a person who’s reeling, never judge him — on anything. He may seem furious or irrational or ungrateful for the blessings he still has. He may cuss or sulk or sob. He may hate on God.

God doesn’t need the likes of you to defend him. Just listen and nod and don’t run off to gossip about what your friend said. He’s in agony. He needs a trustworthy person he can vent to. Be that person. If you think you’d handle matters better if you were in his shoes … be careful. The universe might let you find out.

- If you’re the one who’s suffering, don’t plaster a fake smile on your face. Don’t resort to your own religious bromides. Tell the truth. If you’re hurting, say so. If you’re mad at God, say so. If you’re depressed, say so (and get professional help).

Job doesn’t fake anything. He calls the Lord everything but a milk cow. He relentlessly speaks his pain-wracked version of the situation. And God declares him righteous for it.

- Whether you’re the victim or the friend, don’t wear yourself out trying to understand what’s happened.

Job expends a lot of precious energy agonizing over the why, why, why of it all. As I said, eventually God tells him he’ll never fathom the whys.

Often, tragedy is untelling. You can’t make sense of it no matter how hard you try, so don’t overly try. It just is. We have to accept that to move forward.

- Surrender to God’s sovereignty. Or to whatever you surrender your ego to. Tragedy is the great humbler — that might be its sole virtue. It helps us realize we’re not actually in charge.

We prefer to think we’re masters of our fate, but really we’re all floating on what novelist James Still called this great river of earth, being carried wherever it takes us. Learning our own powerlessness can teach us compassion for our fellow travelers. They’re powerless, too. They’re confused, too. They’re scared, too.

- Pray for everyone in and around the tragedy you’re in, even the knotheads who, like Job’s friends, have made it worse with their tone-deafness and inability to be real. As one beautiful song says, we all need a little mercy now. Nothing is truer than that. Let your pain and newfound humility form you into a conduit of intercession for others’ suffering.

–Paul Prather has been a rural Pentecostal pastor in Kentucky for more than 40 years. Also a journalist, he was The Lexington Herald-Leader’s staff religion writer in the 1990s, before leaving to devote his full time to the ministry. He now writes a regular column about faith and religion for the Herald-Leader, where this column first appeared. Prather’s written four books. You can email him at pratpd@yahoo.com.

Metro Voice News Celebrating Faith, Family & Community

Metro Voice News Celebrating Faith, Family & Community